I wake up to the sound of the helicopter’s blades chopping the air.

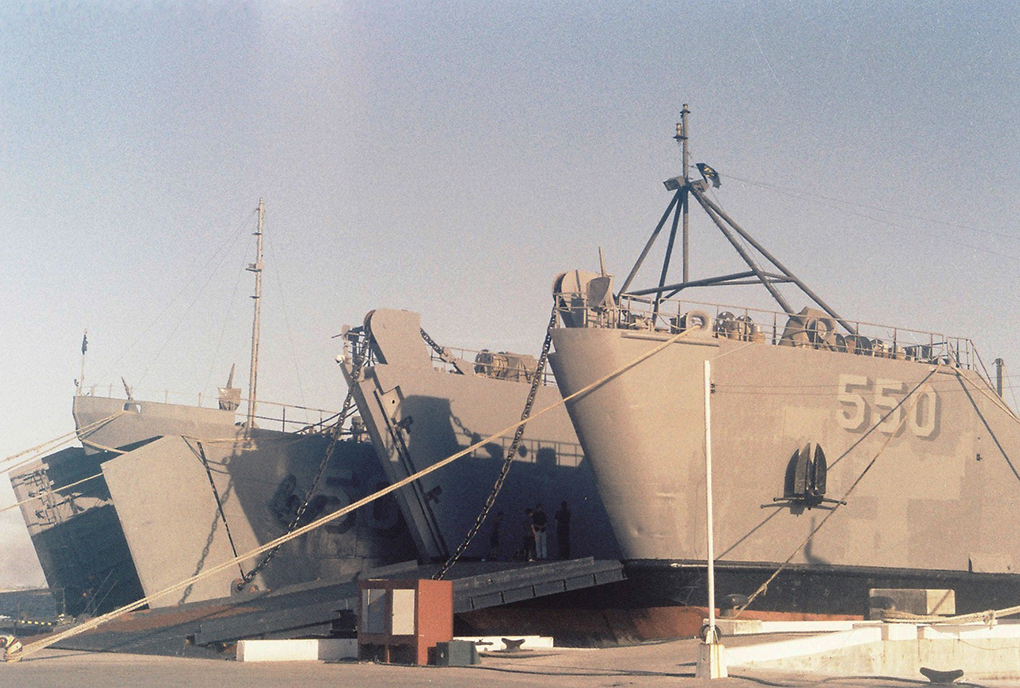

Sangley Point is a name that’s been mentioned at least once in your grade school textbooks. It was once a place for the Spanish to trade with the Chinese, then a naval base for the Spanish and the Americans. It was eventually turned over to us in 1971.

Big military trucks, airplanes, and large ships were all around us in Sangley. It was a naval station and an Air Force base, after all, and it definitely looked like it. Men and women in uniforms were everywhere—enlisted men in jumpsuits, officers with all sorts of pins on their uniforms, men riding motorbikes in their camouflaged pants.

But we would see them go inside our homes and take off their uniforms and wear their pambahay. They were our neighbors and our own parents. There was nothing unsettling about the loud chopper noises and the blaring sirens. It was the same as the shouting we would hear from the sabungan on Sundays; they were all just sounds of our every day.

I moved a lot when I was younger.

I was born in Baguio where my grandparents were born. Then my family drifted to alienating, noisy Manila, where I spent most days inside our apartment, looking at the street for my father’s sedan, waiting for him to come home. We eventually ended up at Sangley Point, which was at the tip of the peninsula of Cavite City.

It was in Sangley that I finally rooted myself in a place without fear of leaving as soon as I had grown comfortable. Friendships are easily made when you’re young, but harder to keep as time goes by.

I remember a friend I met one afternoon at a beach near Pangasinan, where my grandfather used to go to visit the chapels there, as he was a preacher. He was playing with the sand and my grandfather told me to go play with the stranger. We were young—six or seven—but we built sandcastles as tall as we were until the end of the day. After sunset, he went back to his castle of a house that towered over the chapel my grandfather and I were staying in for the night (he would deliver a sermon at the chapel the next day). I did not see him again, and the bitter sting of lost friendships, however brief, left a bad taste in my mouth.

The summers of my childhood were long.

I knew a particular summer would be great because every kid on the block was out in the park in the afternoon until late at night. The entrance to the park was directly in front of my house and I could almost see everyone from my parents’ room on the second floor.

The park was called Lolita Park back then, and it was in Lolita Park that my summer adventures would take place. Kids were swinging around the monkey bars or climbing the top of the slide or teetering on the seesaw or standing on the seat of the swings that had chains as high as my house. There were kids sitting on the grass and people on the basketball court and maybe some grownups walking their dogs while looking after their children.

I’m not sure which days happened when, but they happened.

There were days when the whole neighborhood kids who had bikes would gather in the middle of the park and we would race our bikes round and round the park. There were days I would take my family’s bare sidecar to the commissary to buy groceries. I would also take the same sidecar to the apartment/sari-sari store at the end of the street to spend my entire 20 pesos on a pack of snacks. There were whole afternoons spent playing basketball until either of my parents came home and it was time to have dinner. I would come home with bruises and little cuts. I smelled like the sun.

The houses at Sangley were very American: lots of space in the front yard, and the interiors were spaced out. It was enough for our family of seven, including one helper and one dog, Sabre.

The garage could hold at least two cars and in front we had enough space to host a good party. There was a tree old enough to grow wide branches to provide shade in front of the house. During the rainy season, the same tree would drop huge seeds encased in these shells that, when broken in half, would take the shape of a little boat.

We would put leaves and flowers in the hollow part of these seed-boats and we would float them around the puddles that would form when it rained hard. Sometimes we would go to the little pier and drop them there. We bid each one farewell, waving our hands and maybe even blowing a kiss or two at these little boats for their big voyage to the unknown. We would never see them again. We would forget about them after a few days.

The best summer of my pre-teen life was probably this:

After the school term officially ended, my friends Tetchai and Clinton and I met in front of my house and decided to make paper planes. We pulled up a table and had a stack of white bond paper and we would make all sorts of paper airplanes based on what I had learned during my breaks at school. We used pens and pencils to roll on the wings of the airplanes we made to form curls and folds and even little cuts. These changes made the paper airplanes fly all sorts of ways. The wind was just right and the sun wasn’t as high and after our little workshop we each took our little planes to the sky.

I swear I had this one airplane that could make three perfect circles in the air before it landed. And I had another that would return to me like a boomerang. And I had another that would stay in the air for a solid minute before it landed. I swear it did; I even counted it down once or twice.

The house in Sangley Point is just a memory.

If I could live in my writing, I would. My youth in Sangley always presented itself as a film: orange-washed, lens flare abounding, stark light on brown skin and toothy smiles, snippets of sunsets and green grass and the sound of the sea.

But the memories my families and friends have, no matter how numerous, how vivid, will never be the truest account of what happened. The house still remains, of course, but it is my house no more. Tetchai and Clinton have grown up. The waves in the pier near our house have subsided. Before we moved in, memories had already been made there by someone else, and now that we have left, someone new occupies the house and continues to make memories there.

This story was originally published in our May-June 2017 issue and has been edited for web.

photography by Yuuki Uchida