When was the last time you’ve held a map? You’ve probably consulted a digital map on your way to an unfamiliar location last night. For some, the last time would probably be in your last history or international relations class in college. On a regular basis, we rely on maps to find directions. At the same time, we also neglect its ability to help us in other times of need.

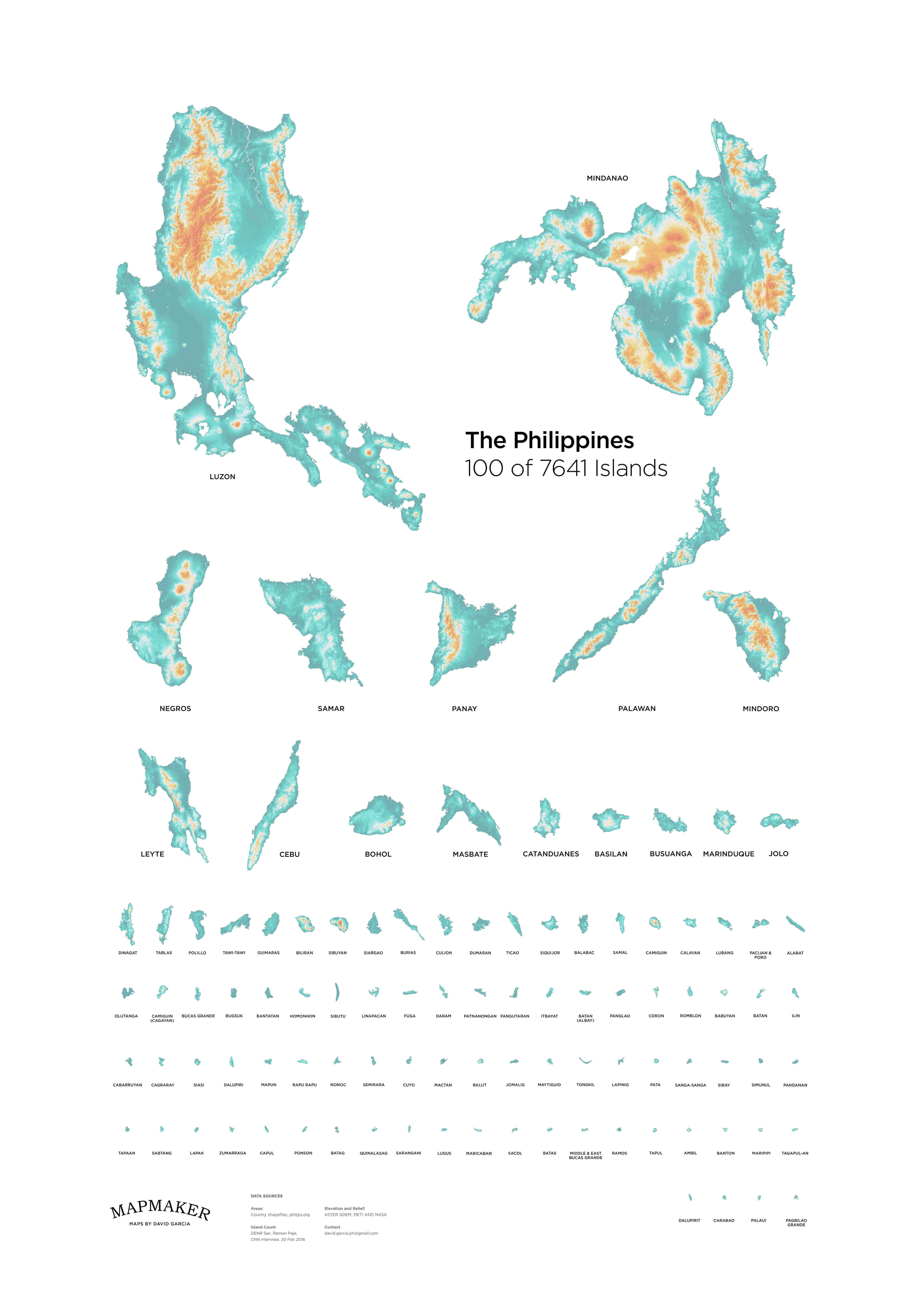

Recently, a friend shared a map showing the largest islands of the Philippines from a page called Mapmaker. It piqued my curiosity. Upon checking the page, I discovered maps that are not simply showing places. Instead, the maps on the page chart the routes of cyclones and earthquakes in the Philippines. The man behind the page is geographer and urban planner David Garcia, who’s taking his masters on geospatial analysis at the University College London.

According to Garcia, he has always had the desire to have an accessible platform for assessing hazards. However, what really drove him to put up Mapmaker was when Typhoon Yolanda hit the Philippines. After the typhoon, he volunteered in mapping and planning with the local government of Guian and then the United Nations. From there, he continued creating maps that would be useful to a calamity-prone country like ours.

What is cartography and why is it important?

For a long time, cartography was called the science and art of making maps and charts. But there’s a nice, alternative view of what cartography is: It’s really about making an argument (this definition was proposed by Denis Wood). When you look at a map of a country, the maker tries to convince you that all the islands you see on the map are part of the national territory. When you study a map of geohazards, the maker is trying to persuade you to think of the hazards that might affect you (and possibly act on them). When you dig up the title of your real estate property, the map there was made to prove to you that it is your land. When you use Google Maps to ask for directions, the results that the interface returns is trying to convince you to take that particular route. When you think of cartography as something in that way, then its importance becomes clearer: it helps “prove a point”. When a map helps in communicating a claim, the reader can explore more ideas, think about issues, and take action.

What’s the idea behind Mapmaker?

Here was the problem I was trying to address: in the popular imagination, geography looks like a traditional and frozen field. On the other hand, “geospatial analysis” and urban planning sounded complicated and elitist. My colleagues and I understood each other so well. But that meant that we were merely preaching to one another, the converted. In contrast, I wanted a platform on spatial matters that people, in general, can relate to.

The core idea was to create a channel where I can help citizens think about themselves and society in a spatial way. Through maps, I’d like to promote both basic ideas on openness and important geographical issues. For example, in the “100 Largest Islands” map, I did not put in the provincial boundaries. I wanted to communicate that there are many things that we have in common and that geography shouldn’t be a reason for us to be divided. About the map on historical cyclones and earthquakes, I wanted to show that there are no completely safe places in the Philippines. There are only places of varying levels of risk and vulnerability, and our capacity to prepare and adapt. It was also about persuading people to rally around issues such as disasters and climate change.

Geography shouldn’t just be about capitals, boundaries, or names of famous places. That view on “what is where” or “where is what” is very limiting. By showing geographical patterns in Mapmaker, I’d like people to ask the why and how behind the what and the where.

I noticed that the maps you make are quite more approachable in terms of design. How important is the design of a map?

In general, the design of a map is the only thing that bridges the ideas of the mapmaker with the audience. It’s comparable with the reasons why writers must forge clear and compelling sentences. I remember what Marshall McLuhan claimed: “The medium is the message.”

The maps that I make look simple, but they take long hours to think about, test, and build. There’s a lot of searching, data cleaning, and iterating. There’s a lot of feelings, affect, and emotions, too, due to personal experience. I usually make maps on geohazards and risks because of the suffering I encountered in places hit by disaster and conflict. I motivate myself with such experience and turn bad experiences into useful maps.

Studying the Philippine archipelago and its islands, what are the common mistakes you see in the maps available?

My knowledge about Philippine geography has limits, but here are three general observations I have on the question. They’re about quality, usability, and openness.

First, I think that there is a general lack of quality in maps that are available. That lack of quality means that some places are missing or that there are errors. For example, during the Haiyan response in Tacloban we found out that even San Juanico Bridge (the largest and longest bridge in the region) is not in the official maps. Several place names were also incorrect. On the side of the commercial map providers, a lot of houses in vulnerable communities are “invisible” because the providers can’t make profit with such data (as opposed to data in major cities). How can we plan if the infrastructure is missing and communities are invisible on the map?

Second, I think that such issues on data quality affect the usability of the maps. Let’s say we are in a community meeting to discuss disaster preparedness or urban health issues. If the residents don’t even see their homes in the map, then it will be difficult for them to better understand and make decisions based on the data. Furthermore, the lack of usability erodes the trust in the geographic information.

Finally, there will still be issues even if the data is accurate and complete. Generally, there is a significant amount of data that exists in the databases of the government. The major hindrance is that the geographic data is not free, open, or accessible. During the Haiyan response, there were times when we had to wait for months for our requests to be accommodated by the national government. There were times when we had quick access to the data, but we had to do a significant amount of unnecessary reprocessing because they were in closed formats (e.g. pdfs), which is not good for analysis. The goal was to make print maps, the most accessible format for far-flung communities with no internet.

What have you learned about the Philippines through cartography?

There are no completely safe places in the Philippines. There are only places of varying risks and vulnerabilities, and the people’s capacity to prepare and adapt.

What are your goals for Mapmaker?

For me, I would just like to keep making maps that people would find useful and enjoy the process. I’d like Mapmaker to be an invitation for people to treat geography as part of their way of life.

I won’t forget my favorite quote from David Harvey: “Geography is too important to be left to geographers.”

Read more:

How to save the environment, according to Marianna Vargas

The solution to Manila’s traffic problem may be in Pasig River

Pasig River is the second worst plastic waste contributor in the world