A film or TV drama set is often chaotic. The one for this afternoon drama, however, is unbelievably calm: Actor Carlo Aquino can walk in and out of the set without fans halting him for an autograph or a picture; crew members patiently wait for the director’s instructions; and the director placidly watches the rushes or videos taped earlier in the day inside his air-conditioned tent.

Any emotional or mental whirlwind is suppressed by every person on set. There are still a few day scenes left to shoot, but daylight is fading fast and gray clouds hover over this side of the city. This doesn’t bother cinematographer Neil Daza, however; he has been capturing both moving and still images for 25 years under myriad conditions. He sits quietly in one corner of the tent, observing the director watch the rushes.

Natural path

“Since I was 13 years old, I’ve always had a camera with me,” Daza reveals. Yet cinematography wasn’t what he had initially wanted to do. In college, he majored in fine arts, with the intention to become a painter one day. However, after graduation, he took up his camera again and became a photojournalist for the broadsheet Malaya.

Daza stumbled upon cinematography (quite literally) by accident. “I had an accident, so I had to stop working and shooting for a year.” The hiatus from photojournalism led him to a filmmaking workshop at the Mowelfund Film Institute in 1991.

Daza then began shooting films with a 16mm camera, doing alternative and experimental short films with his colleagues. “There’s more thrill in working with film. Nobody really knows what images will show up whenever you go into the viewing room,” he says. “That’s what’s missing today, the different kind of excitement from shooting on film. Cinematographers get to have more control over what will be shown on screen because they alone know what will show up.”

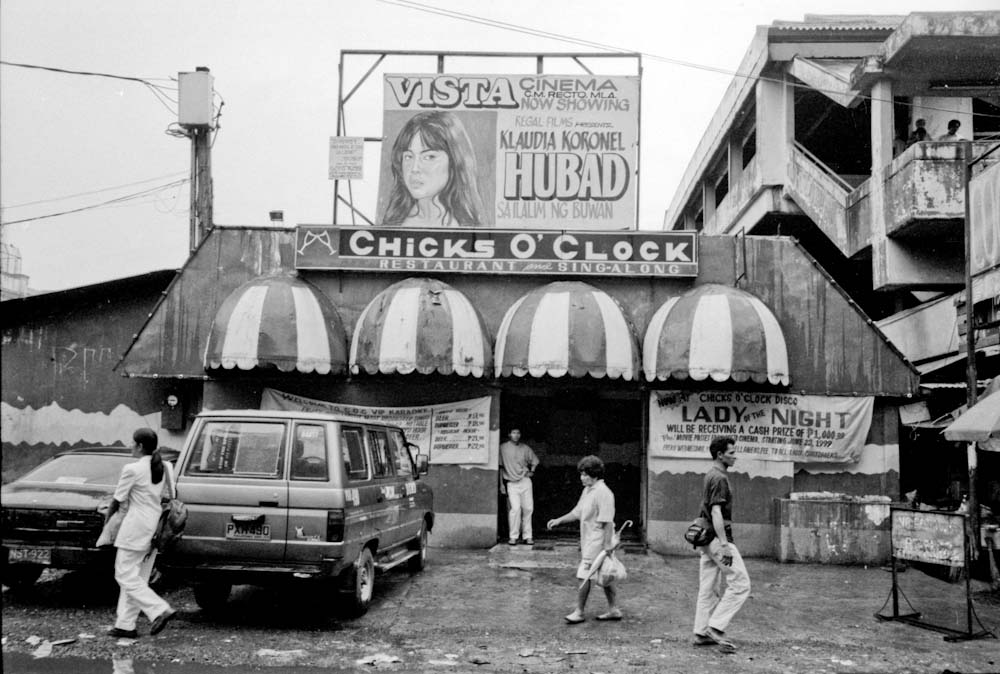

The era of music video ushered in new opportunities for Daza as a professional cinematographer. He shot music videos for OPM hits Kung Ayaw Mo, Huwag Mo and Nerbyoso by Rivermaya, and Harana by Parokya ni Edgar. “Sometimes, in order to shoot on film, we take on a whole project and cut down our talent fees so we can buy negatives and shoot the music video.” He recalls having the comedians Jun Sabayton and the late Tado Jimenez as production assistants and bit players in music videos he had shot in the past.

Full frame

Director Chito S. Roño, also the manager of Rivermaya, was about to make his comeback film in 2000, Laro sa Baga, after a short hiatus. He was looking for a new production designer and a cinematographer to work with, and since Daza had already worked with Rivermaya, Roño got him to shoot the film. Although he had shot scenes for Mike de Leon’s Bayaning Third World before this project, Daza considers Laro sa Baga as his first full-length film.

Roño became a constant collaborator. In fact, they just recently shot a new independent film that’s ambitious enough to incorporate computer graphics. Aside from Roño, Daza has also worked with the late director Francis Xavier Pasion in Sampaguita and Bwaya, which he considers one of the most difficult films to shoot.

Entirely shot in Agusan, Bwaya is a docu-drama about a woman who lost her daughter to a crocodile. Daza cites logistics as the source of difficulty, since there was no electricity in the location and most of the scenes were shot on a boat. “I improvised with Chinese lanterns. Our only source of power was a car battery. Every morning, we’d bring a portable generator. Of course, one by one, the [sources of] light would disappear, so, we’d hope to finish everything before the power runs out,” he recalls.

“Cinematography is not just painting [a scene]. It has to connect with the characters and the whole narrative. That’s the hardest part,” Daza says. While it’s good to have a breathtaking shot, a film cannot live on one specific scene or shot alone. “You have to see it as a whole film. The challenge in feature film cinematography is consistency: You have this idea, you have this visual treatment. Does it show from the start to the very end?”

Rule of singularity

A film or TV set is chaotic, Daza admits. Here, the director is god. And when he says, “Let there be light,” no matter what it takes, there should be light. In between takes, Daza finds his much-needed peace. Those brief moments amid the pandemonium are when he returns to his roots. “I always bring my still camera even when I’m shooting films,” he says.

With his still camera, whether film or digital, he captures the most interesting scenes that never make it to the final product: actors in their most unguarded moments, crew members who hadn’t slept for days, and the environment in its most natural state. Forty images from probably hundreds or thousands of photographs he has taken in the past 25 years will be shown in the exhibition “25 Times: Images From Behind the Camera” at the Cultural Center of the Philippines from Aug. 3 to Sept. 10.

“One of my favorite pictures is of Mystica’s hand. She was on bed and we were talking during setup time. I noticed her hand because she had really long nails,” he recalls. The image doesn’t show much, but it’s poetic.

“Still photography has a different kind of magic when you freeze the moment; motion picture doesn’t have that. Also, with photography, you can work alone.” he explains. “I think that’s the reason why I never left it behind. Filmmaking is a chaotic and collaborative medium with creative people and producers.”

If he has learned anything from the latter, more complicated medium, it’s compromise. “Filmmaking has a business side to it, it’s not just art. If you want to pursue simply art, then go paint at home,” he says. “But there’s a thin line between compromise and sellouts. You have to know where to stand. It doesn’t matter whether [what you’re filming is a] mainstream or indie [film].”

While taking photographs in between scenes provides him solitude, Daza still intends to return to his first love. “I’ve started drawing again. I bought a canvas, but it’s still a canvas,” he says. “I just need to find the time [to actually paint].” Working in film for 25 years inevitably gave him hellish times, which he acknowledges, yet it seems he’s in it for an even longer haul. If there is anything that keeps him going, it’s his love for his craft.

The sun has finally set. Daza looks out the window and sees a whole new setup. “Why is there a butterfly?” he wonders. A white sheet has been put up on set; in the approaching darkness, his team finally found a way to create light.

This story originally appeared in Southern Living, August 2017.

Read more:

Veteran cinematographer Neil Daza on shooting music videos for Rivermaya and Parokya ni Edgar

How Brilliante Mendoza is saving Philippine cinema

Remembering the Manila Metropolitan Theater

Why do local films flop?

Five books from Petersen Vargas’ bookshelf