By Sara Isabelle Pacia

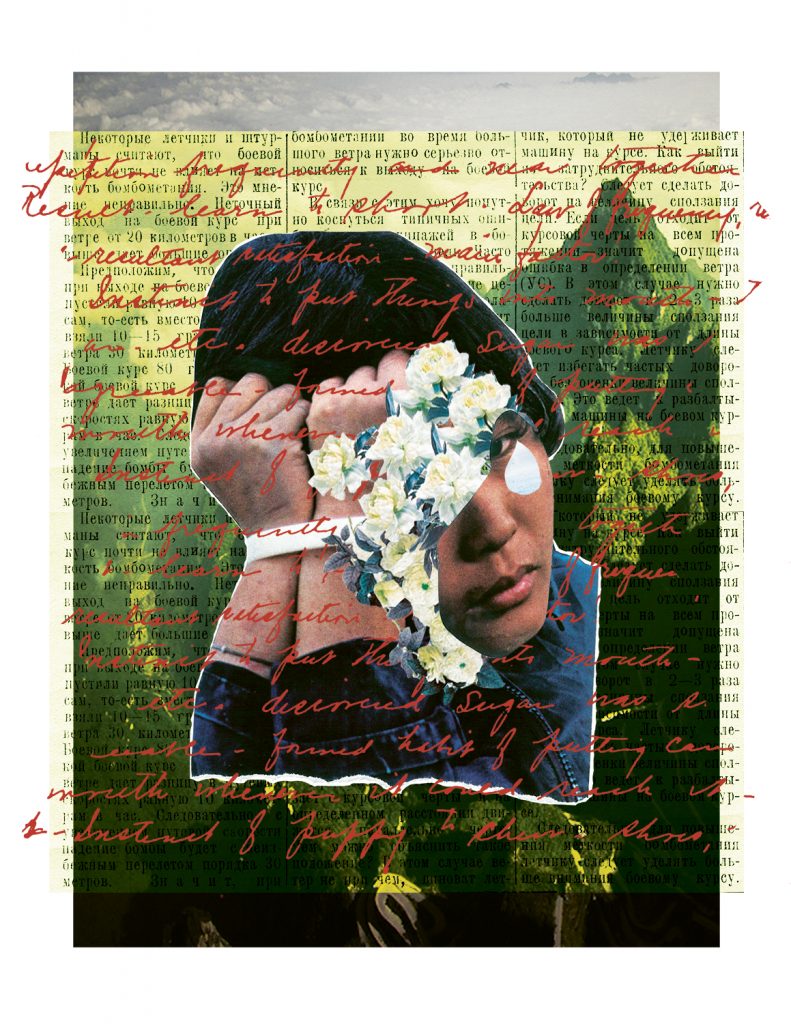

Illustration by Grace de Luna

Twenty-six-year-old Philippine Daily Inquirer digital content editor Sara Isabelle Pacia describes the harrowing task of recording everyone who’s perished in the first six months (and counting) of President Duterte’s bloody war on drugs.

Her name was Althea Fhem Barbon, four years old. She lived in Guihulngan City, Negros Oriental, and went to school at Gucce Learning Center.

On the night of August 31, Althea was on the back of a motorbike, seated behind her father, when she was killed by policemen–the kind she wanted to be when she grew up–who were hunting down her father, a carpenter and suspected drug pusher. The police behind the buy-bust operation said they had first bought P500 worth of “shabu” (methamphetamine hydrochloride) to prove their suspicions, that Alrick shot first in an attempt to flee, that they fired back only in retaliation. The policemen said they would not have shot if they had known Althea was hiding behind her father.

“We regret a lot that [a child was killed] when she was not the target. Had we seen the child, we would not have pushed through with the operation. We would have cancelled it,” Supt. D’Artagnan Denila Katalbas Jr., Guihulngan police chief, had told the Philippine Daily Inquirer. “We, policemen, are humans,” he added. “We are not animals.”

Her name was Althea Fhem Barbon, the youngest recorded casualty in the war on drugs being waged by President Duterte. Hers is the name at the tip of my tongue in the middle of the night, whose story I want to share over and over again in reply to anyone who justifies the ongoing bloodbath as a sign of progress.

Katalbas says the policemen who hunt down drug suspects are human. But so are the small-time pushers and dealers they deprive of a fair trial. They, too, are not animals, but in the flurry of curses and rewards for the most number of suspects killed, are they really counting?

Her name was Althea Fhem Barbon. She was only in kindergarten.

My name is Sara Isabelle Pacia, 26 years old, and I am the editor of the Inquirer’s “Kill List.”

The Kill List is how the Inquirer seeks to tell the names and stories of the countless who, whether guilty of the crimes they died for or an unfortunate casualty, were never given their chance to defend their name. The list is accessible online, at inq.news/kill-list, and is updated twice a week.

As of Nov. 24, 2016, the Inquirer has monitored 1,657 deaths since noon on June 30, exactly when President Duterte was sworn into office on an iron-fisted platform of change. Of that number, 902 were killed in police operations and 755 others killed by vigilantes, majority of whom wear hoods to hide their identities and ride motorcycles for a quick escape. On average, the Inquirer counts about 30 or so drug-related deaths a day.

Every Monday and Thursday, I collate the reports given by reporters and correspondents on the field into a master list, segregating details such as time and place and possessions to find patterns and trends to highlight per update.

The task of updating what has become a reference for human rights advocates and international agencies is one I consider a privilege and a burden. I am but one journalist doing my due diligence, but more than once it had been me who faced policymakers and those from the private sector asking about the current all-out war on drugs. To directly provide the public with information and give context to recent events has been enlightening and humbling, to say the least.

But every update continues to be a teetering balancing act between detaching oneself to stay objective (as any journalist should be) and feeling too much in order to accurately convey the purpose of the list in the first place.

Sometimes, I comb profile after profile on Facebook to find out more about the dead and the families they’ve left behind. I did this once, when the Inquirer wrote profiles on the SAF44, and I continue to do it today for some victims of the drug war. (It’s surprising what you can find with just a little stalking savvy.) Sometimes, too, I put myself in the shoes of the families left behind. What if it were my father or brother or friend who was killed?

Every single day, I struggle between the journalist’s obsession with objectivity and detachment, and my own innate nature to speak up and share what I really, truly feel about all this bloodshed. To write this essay is part of this struggle: What if, by speaking up, I am compromising the Kill List’s integrity?

Or, perhaps something worse (and infinitely more selfish): what if, by continuing to update the Kill List, I am only torturing myself for an audience that maybe no longer wishes to listen?

I face only the names and stories given by our reporters and correspondents, and there are days when I am admittedly grateful that I get to do this in the comforts of the newsroom instead of out on the field late at night like many of my colleagues. But editing and contextualizing from afar the unprecedented execution of drug suspects has its own battles.

The gravity of what I do hits hardest in the minutes right before sleep takes its hold. Instead of sheep jumping over a fence, names after names come barging in one after another until my eyes are wide open and breathing becomes a chore.

[pull_quote]“The gravity of what I do hits hardest in the minutes right before sleep. Names after names come banging in until my eyes are wide open and breathing becomes a chore.”[/pull_quote]

When this happens, I ask myself over, and over, and over again: Is this job worth it?

To put myself back to sleep, I recount the four passages of what should be every journalist’s Bible: the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics.

Am I seeking the truth and report it? Yes. A thousand times yes.

Am I minimizing harm? Sensitive details are omitted to ensure that no copycats or sensationalists can use what is published to their benefit.

Am I acting independently? All data collated are from’s own stories, and no other data can be added or subtracted to influence the numbers.

Am I accountable and transparent? While the master document is not available to the public, I and the Inquirer have never shied away from disclosing our process in compiling the Kill List—even from Senate inquiries.

Is this job worth it? It must be. It has to be.

Their names are “Unidentified suspected drug pushers #4 and #5.”

This is how the Kill List labels two men from Quiapo, Manila, found dead at 3:20 a.m. on July 3 with a sign on their bodies saying, “Pusher.” They were the first case of extrajudicial killings monitored by the Inquirer and perhaps pioneers of the now infamous “cardboard justice,” or when the dead are found with placards labeling them drug pushers that should not be emulated.

Today, the Philippine National Police is reporting that there are 3,370 drug personalities who are labeled “deaths under investigation”–DUI for short. These are the drug-related deaths being credited to masked gunmen who PNP Director General Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa says could either be hitmen paid by drug lords or even policemen covering up their own drug dealings.

That number is much, much more than the 755 or the 1,657 the Kill List has tracked, proof that while the numbers the Inquirer is reporting is already alarming in itself, the truth is much, much more terrifying.

Today, Suspects #4 and #5 are still unnamed.

Since the Inquirer began updating the list, detractors have been quick to denounce it as a rootless campaign aimed at attacking the President without basis. One senator, in particular, even went on a media blitz denouncing the figures, saying past administrations had more deaths in a shorter span of time and media was just being selective.

But I always hit back: When else in Philippine history did its President openly encourage the deaths of these pushers he deems as not human, and celebrate every death as a victory in his all-out war? When else in our recent history did police use “nanlaban” or “in self-defense” daily in their spot reports, or did finding a dead body or two in your neighborhood become increasingly common?

(And to that senator, I implore him to get his facts straight. The higher figures that he has been presenting as proof of his defense are figures collating all kinds of deaths during the previous administration–not solely drug-related ones like the Kill List’s.)

In writing this essay, the journalist in me is protesting the lack of objectivity. But no matter my duty to report only the truth to the public, I cannot deny forever the sadness and grief and anger at how the current administration would prefer to simplify an issue that is far from simple.

I am a firm believer in the goodness of people, and I believe in three things: one, the drug problem is rooted in poverty. Two, it won’t go away no matter how many pushers the police kill off. And three, rehabilitation and institutional support should be what the administration is focused on.

These three things, I wish I could shout to the world–or at least online. But at the end of the day, I know the best and most effective form of protest is in what I am currently doing–with facts and with information.

To update the Kill List on a weekly basis is my own protest against the organized execution of drug suspects before their day in court. Doing this is my own way of shouting to the world that there are people who are looking into this and won’t look away from the bloodshed, no matter how absurd it gets (what’s next, the death penalty for mere drug possession?).

And you know what? No matter how many times my heart breaks at every name I input, I can only pray that this task never gets easier because, while painful, this exact heartbreak is proof that this execution without fair trial is something that I nor anyone should get used to–as it should be.

My name is Sara Isabelle Pacia, and don’t expect the Kill List to stop any time soon.

Read the Inquirer Kill List, updated every Monday and Thursday, at https://inq.news/kill-list.

This article was originally published in our January-February 2017 issue and has been edited for web. View the full issue online here. For physical copies, our delivery locations are listed here.