Mention films from Southeast Asia and the first things that pop to mind are the horror films of Japan, the fantasy movies of China, and the Bollywood musicals of India.

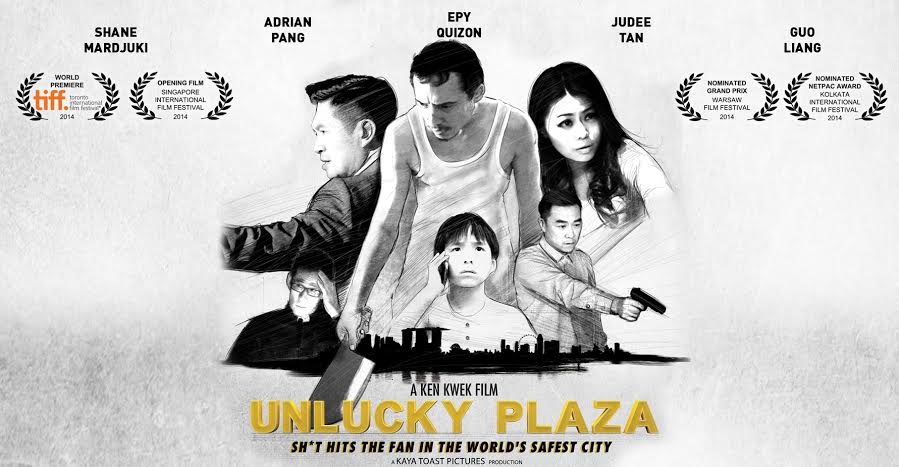

When I think about Southeast Asian cinema… well, the thing is, I don’t. I don’t think about Myanmar. I don’t think about Thailand. I do think about Singapore, but only because of that one indie film starring Epi Quizon. I believe it was Unlucky Plaza.

Unlucky Plaza starred two Filipino actors: an unnamed maid and, of course, Quizon, playing the role of a struggling single father. The film tackled poverty and politics, complete with a weird sort of disjointed plot and several shaky camera angles. It had everything you would expect from a stereotypical Asian indie film.

Enter Tingin ASEAN Film Festival organized by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) last October in celebration of the Philippines’ 50th anniversary as an ASEAN member. Tingin is the first film festival to collate the best of Southeast Asian cinema. During the press launch, NCCA international affairs head Anne Luis said they also hope to develop the audience for these regional films.

So, what exactly can the audience expect from Southeast Asia (according to Tingin, at least)? The answer seems to be my initial impression: poverty porn.

From government-approved official selections to the Piolo Pascual-handpicked tastemaker selection, every film in the roster bore a stark, politically-charged background. Whether an ex-convict trying to build a new life after prison or the coming-of-age of two brothers in a small village in Vietnam, every storyline boils down to politics and poverty.

During the festival, I caught up with film critic and University of the Philippines Film Institute professor Patrick Campos to discuss this issue. Is poverty porn really all Southeast Asia has to offer?

Do you think that Southeast Asia, as a collective, has more to offer than just poverty porn films?

Ang ganda ng premise mo, as a collective. But the collective that is Southeast Asian cinema is not a reality yet. We’re still trying to find our way to each other and with each other. Ngayon pa lang naman nagkakakilala ‘yung mga filmmakers because in the past, the gates [and] the borders have been closed. We couldn’t understand each other.

So ngayon pa lang nagbubukas. Hindi pa natin alam kung ano ‘yung magiging itsura niya. And what makes it interesting is kahit wala pang collective, some of these poverty films are there. Which makes us say, “Wow, ganun din pala ‘yung kwento nyo!”

It’s a common truth that’s shared, but it’s not a regional concept yet. It’s still within [our respective] borders that we’re making [these films]. So the question of ano ba magiging itsura ng Southeast Asian cinema kung magiging collective tayo, we have yet to see that.

There is still that common thread of producing poverty porn or films. What are your thoughts on that?

The concept of poverty porn must be contextualized. For example, in the Philippines, we have a very rich tradition of political films that feature poverty. So when we speak of poverty porn, we all know what we’re talking about.

When we do find them in other Southeast Asian countries, they’re usually an eye-opener. In other places, they have smaller [film] industries or cinemas. They hardly make films about poverty. It’s next to impossible to see a film in Singapore about poverty, right? So when they suddenly make a film about poverty, it would be very hard to call that poverty porn. Some cinemas are so small that for the whole history of their cinema, less than 20 films pa lang ‘yung nagagawa nila. So when they make a poverty film, it’s like a splash.

The thing with poverty films is they never really go away until poverty goes away. Because films about human trafficking, violence against women that appear so depressing, that really happened. In Southeast Asia, napaka-talamak. So it’s necessary to make them, and you have that interesting tension between wanting to promote an image of a place and actual reality.

But then what do you say to those who believe we should stop making poverty films because it’s detrimental to the image of our country or region?

In some of my more recent works I’ve actually been speaking against romanticizing poverty. Ang mahalaga naman sa’kin, [is if] the films are speaking to and for the people. And our main problem in the Philippines is sometimes we produce more films about poverty than what actually reaches our own people or does anything for them. [That’s when] it becomes really problematic.

Not to say they should stop. My point is, we should make it effective. It should affect change. If we don’t do anything like that anymore, we will wonder why do we keep making it?

I think it’s erroneous to compare our experience to Hollywood. Hollywood is a hegemonic monster. They export to the whole world. Their stories end up being our stories, which should not be. We should be telling our own stories. So hindi pwede i-compare, I think. The challenge really for the Filipino artist is how do we make it new. We should be able to tell our stories in a way that isn’t detrimental to our own people.

Do you think there’s room for more commercial films in the Philippines?

Definitely. I think nandun nga tayo sa kasalukuyan. Most people complain that ‘walang ganito, walang ganyan,’ but if you look at it historically, matagal na nating pinaglalaban. Actually, we are in a new phase where these “pop films” that you call which we could describe as middle brow, more intelligent niche films, it’s now their time. Our forebearers, filmmakers before us, activists before us, they were clearing spaces bit by bit. And now, we see it blossoming before us.

So I think there will be a lot of variety. Pero struggle pa rin siya. In certain places, there will be a struggle between gatekeepers, distributors, artists, filmmakers, and audiences. What’s important is while we pine for more intelligent films, we also should encourage the viewers. Because sometimes when we say ‘nakakabobo ‘yung pelikula,’ what we say is the viewers are stupid. We shouldn’t talk down or condescend the people who like films that we think are stupid. It’s economics, it’s politics. Kung ‘yung mga manonood mo mga hindi nakapag-aral, walang pampanood pero ‘yung mga nagrereklamo may pampanood, there’s a clear divide.

You cannot generalize that there’s something wrong with poverty porn. As it is, there’s a reason why poverty porn exists. You have to look at each experience, at each space. Walang panglahat na sagot.

Photos courtesy of Facebook.com, CulturalCenter.gov.ph and Mothership.sg

Read more:

Corruption returns to Metro Manila Film Festival, according to Citizen Jake director

It’s all about Southeast Asia in the first TINGIN Asean Film Festival