by Chryssa Celestino

Three degree Celsius weather in Seoul usually calls for hangouts indoors with a space heater. But on this particular day in November, my friend and I rail-biked along the repurposed tracks of Gyeongchun Line at the Gangchon Rail Park, at a height where the wind crept around our necks and numbed our faces like a free Botox treatment. We pedaled our four-seater car with David, our Korean tour guide, into one of the attraction’s tunnels, where a remix of Gangnam Style played. Funky strobe lights cut through this stretch of darkness and in here, it was easy to forget we were uphill, overlooking a province, but much easier to imagine we were being sucked into a vortex where life is as glamorous as Big Bang’s music video sets.

Outside this tunnel was a bigger fantasy. At the foot of this land and miles away from it were clean, hyperconnected cities with subway toilets that included an emergency call button (which I stupidly pressed once thinking it was a hand sanitizer box), streets safe enough to grab spicy rice cakes from at night, and three-story beauty shops themed like hotels complete with lipstick buffets and a bed.

People here—the urbanites, at least—wore this year’s Pantone colors and paraded their pert, healthy perms. Never a dyed hair out of place, and if there were, beanies and sleek fedoras hid them from view. If a facial flaw suddenly seemed inhibiting, plastic surgery clinics offered cheap cosmetic solutions for one’s dwindling self-esteem. Ads for the clinics were plastered in subway stations, calling out to my less-than-sharp nose and hormonal chin acne. Food, too, got a makeover: burgers were stuffed with breaded mozzarella patties—fried cheese, you guys!—and sparkling water sometimes came with rose petals and a pink hue.

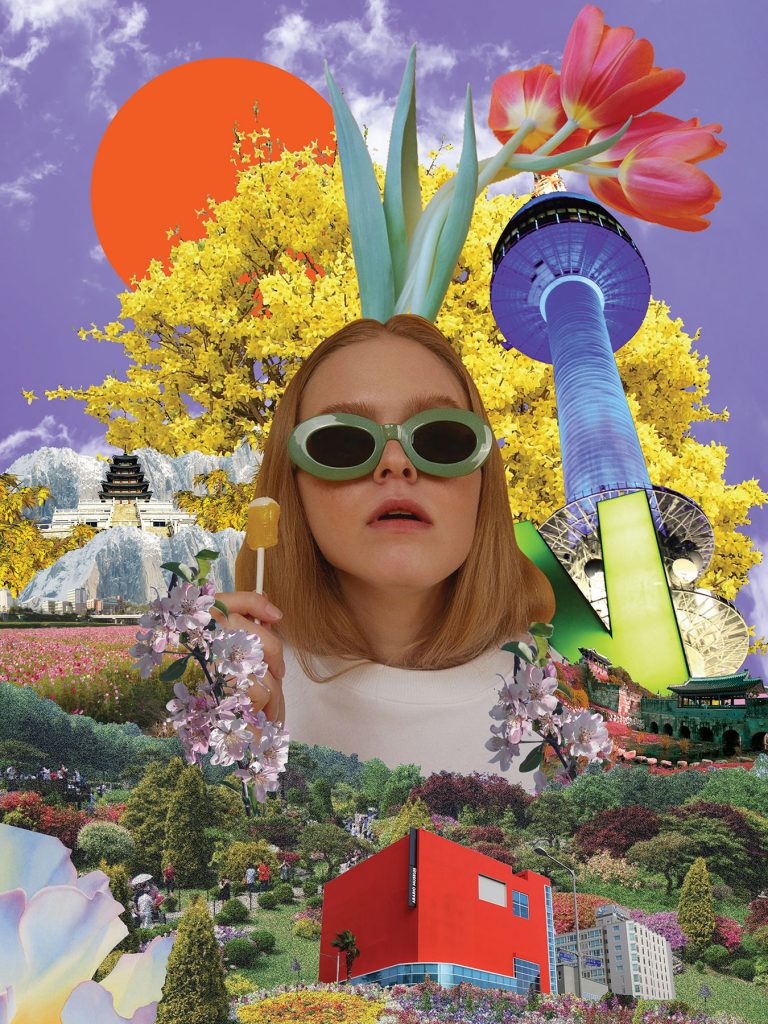

South Korea, like what K-pop taught me, is a pretty dream asking to be lived. You don’t even have to fantasize about kimchi.

“South Korea, like what K-pop taught me, is a pretty dream asking to be lived. You don’t even have to fantasize about kimchi.”

Aside from being one of the perfect times to visit the country—fall here was red, as Taylor Swift would sing—this time around November was when Donald Trump won the U.S. elections and Ferdinand Marcos was sneakily buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. SoKor was the perfect place to start forgetting. Or at least, block out all the bull that was happening beyond it.

When we pedaled our way through the tunnel’s exit, leaving PSY, the lights, and our K-pop star fantasies, we were asked to hop off at the nearby station and wait for the train that would take us back down to where we started. This stopover offered a sweeping view of the land down under: a light fog blanketed the province below, the gray-blue sky looked icy but calming, and yellow-green trees stood proud in the cold.

Beside the tracks at our station was a small, active waterfall, which David told us to use as a backdrop for a selfie or two.

“Why aren’t you taking photos?” he asked us, approaching my friend and me in the middle of a cheeseball snacking session. “Don’t you find this place beautiful?”

Beautiful. The word registered like the first time we saw the grounds of Ewha Womans University. My friend took me there on our first day. Before reaching its campus halls, visitors like us were greeted by its famous “Campus Valley,” a long slope of gray pavement dipping then rising to the other end of the strip. Golden trees, flame-red shrubs, and a few green plants framed the manmade vale. Students in their pastel-colored autumn garb scurried in and out of the scene as they took out their fleece-lined hoodies and sought the nearest shade. The rain poured and the clouds cast a grayish tint much like a Gingham filter muting real life’s color palette. In front of us was a moment so VSCO-worthy, no sharpening and saturating were needed. It didn’t matter if walking here was tiring. Screw comfort, we’re getting likes for this!

This was South Korea, aesthetics’ alternative address in Asia, where places like the Dongdaemun Design Plaza—a four-story atypical structure designed not to look like one that exists in Jung-gu—came off more Instagrammable with its quirky curves from the outside than the exhibits it housed. This was where recycled shipping containers found their calling and were erected into a hip shopping mall complex called Common Ground.

Koreans’ reality, it seems, was a photogenic ultramodernity they crafted in just 40 years; we were all damned if we didn’t notice it. Like someone fresh out of a successful rhinoplasty, they might consider it a fail if nobody found them prettier than yesterday.

Maybe looking good here was as much a national duty as it was a choice. When in a land where skincare and cosmetics flow, there’s no resisting the (cleansing) milk and honey (masks) that we’re blessed to use. A trip to Myeongdong, one of Seoul’s primary shopping districts, was an exercise in beauty know-how and self-control. The road shops that lined its many alleys reflected the promises they made to the thousands of tourists flocking to avail a sale. Say, when Etude House sold Lolita imagery through screaming pink interiors, white frilly decors, and a poster of the usually cold-looking Krystal Jung smiling coyly out of character. Or when Laneige’s pristinely clean aesthetic almost convinced us that Song Hye Gyo’s whiteness was achievable for someone pretty yellow.

A culture of appearances loomed and like shopping in this populated space, it was easy to get lost. Easy because the pressure existed like our mothers nagging us to get dressed every morning. Once, when my friend and I were shopping for W4,000 (around P180) concealers, the shop’s saleslady went up to us and offered their latest snail products. Snail mucus filtrate was holy grail status in any Asian beauty believer’s book but that day, we were happy with the makeup we got.

The saleslady seemed determined to sell and quickly pulled us to the corner where the snail serums were. Brushing her bangs aside to reveal her forehead, which was as white and clear as the rest of her face, she started demonstrating in broken English how to use the products. She swiped some of the serum onto my palm and as she rubbed it dry, she looked up and started pointing to my acne. “This, this, this—disappear!” she said, deadpan. Great. Now my troubled skin felt even more foreign.

The pressure to look good seemed to extend to other habits. Couples were a sight in Seoul. We got a glimpse of Korean lovey-doveyness on Pepero Day, their version of Valentine’s with a side of cookie marketing. At the Itaewon station, a guy dropped to his knees to tie his tall girlfriend’s shoes. She was perfectly capable but her boyfriend was apparently more right for the job.

On a different day, on our ferry back from Nami Island, a girl seemed tired of standing and instead of plopping down on the floor and staining her blue coat, she used her squatting boyfriend as a human chair. She happily sat on him, though I could tell from a distance it wasn’t the most comfortable position. But hey, they oozed #relationshipgoals and old-fashioned chivalry was easier on the eyes than a couple eating their faces out for us to see. K-dramas might not have been that far off when depicting cheesy cringe scenes—or maybe it set these expectations for couples to follow because they looked romantic.

Whether the matter was storefronts or gorgeous couples or personal care, citizens and every nook and cranny maintained the image their country seemed conscious to uphold: being a superfluous daydream we couldn’t snap out of.

“Whether the matter was storefronts or gorgeous couples or personal care, citizens and every nook and cranny maintained the image their country seemed conscious to uphold: being a superfluous daydream we couldn’t snap out of.”

“Korea’s so beautiful,” we finally told David on our way back to Seoul after a full day in Nami. He nodded with a straight face, either expecting the praise or maybe pausing to let the compliment sink in. Sitting on the front row of the bus, David looked past the windscreen before confessing with a shrug, “Korea is just… eh.” He turned to us and added, “I want to go to Boracay before I go to the army,” hinting at the mandatory military service every Korean male goes through. “They say the water there is so clear, unlike here in Korea, where it’s pretty dirty.”

I wanted to warn him that Boracay wasn’t what it used to be. That the island was now too populated and polluted, even to locals used to crowded places and dirty environments. But that would be a buzzkill. I remembered that fantasies were personal; they were realities we craved when real life failed to meet our dreams.

South Korea, to me, was both distraction and escape, both wonderland and rabbit hole. While it gave me something to believe in—yes, it was possible to catch up to developed countries in just a matter of years, with some discipline—it also gave me things to ponder. What do you sacrifice to look this good? What do you give up as a nation to become better? Why can’t someone look frumpy for once and still belong to this nation of cool?

“What do you sacrifice to look this good? What do you give up as a nation to become better? Why can’t someone look frumpy for once and still belong to this nation of cool?”

I had to stop myself as soon as I asked. Fantasies shouldn’t make sense most of the time. They were felt, thought, dreamt, but not understood. I’ll wake up to reality next time, but for now, I’ll close my eyes the way I did when I pedaled through that tunnel and imagined joining G-Dragon on his throne on the set of Fantastic Baby.

This article was originally published in our March-April 2017 issue and has been edited for web. View the full issue online here. For physical copies, our delivery locations are listed here.