Jan Vincent Gonzales can’t say the name of a writer without alerting his virtual assistant trapped inside a smart speaker. He runs a global consultancy for Filipino talents, a sort of index. Though if you ask him and many queer Filipinos abroad, they would prefer to be called Filipinx.

A month into quarantine he launched Mercado, the said index, a “digital palengke” for artists, creators, creatives of all fields. He signed photographers both Manila-based and US-based along with artists, illustrators and graphic designers. The name Mercado Vicente combines his mother’s maiden name and his middle name. He did that amid the pandemic, a lifeline for Filipino creatives struggling during this changing time.

“Being creatives means so many different things,” Gonzales, the founder and director of his eponymous agency says. “Stories” is another facet of creativity he wanted to highlight through Mercado Vicente. “Through writing, we want Filipinos all over the world to connect and find similarities within themselves through their stories.”

Minority within a minority

The writer who cannot be named was Alexa Tietjen, who’s also a video producer. She was the first writer to be published under “Stories”, a collection of narratives, words, poems, and other written forms accompanied by visuals on what it means to be Filipino wherever you are in the world—a love letter on the diversity of Filipino experience.

When her story came out, the Filipino community abroad was buzzed with the issue of a white-owned wine bar called Barkada. Gonzales wrote about it in detail, which became technically the first entry in “Stories.” There he writes, “After learning of a new wine bar opened by four white men in Washington D.C. taking this moniker, we had to do something.

“These guys landed on Eater for capitalizing on a Tagalog word. There’s no reason then that we should have any problem with highlighting on the many Filipino establishments that are run by Filipinos.” And list these Filipino-run restaurants he did.

Then there is the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US, which further examines the role and the place of Asian-Americans in the country that’s racially-divided.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

“Through writing, we want Filipinos all over the world to connect and find similarities within themselves through their stories.”

[/one_half][one_half_last padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

Alexa’s story is one of a minority finding a place within a minority in a foreign country. The daughter of a Filipina mother and a German-Swedish father, her identity is often questioned within the very community she seeks refuge in. People ask her, if she is not Chinese, then what is she? A tendency by white folks to conflate all Asian identities into one classification as East Asians makes it even harder for the likes of Alexa.

But as she wrote and Gonzales wants to prove through a diverse collection of writing: there is no one way to be Filipino.

One story at a time

When I spoke to Gonzales over Zoom to talk about this latest addition to their Mercado initiative, it also happened to be Buwan ng Wika in the Philippines, a month-long celebration of the indigenous languages of the country. The topic in itself is highly politicized and polarizing considering there are over 100 languages used in the Philippines’ 7,100+ islands and just one official language based on one used in Luzon particularly in the Tagalog region.

“We push for highlighting the experiences of marginalized voices in our community, especially those of queer folx and womxn.”

Since our conversation, Gonzales’ library of Filipinx experience has expanded—for one, he gleefully shares on his Instagram that the term “Filipinx” has now been added to dictionary.com.

There are now four entries published on “Stories”: Alexa’s reflection on minority identity; Caresse Fernandez’s poem anchored on her lola’s dark lips; Will Conlu’s “Eat, Pray, Love”-esque journey amid the pandemic; and a Q&A by Gonzales and Cirillo Torres with filmmaker Isabel Sandoval on her ground-breaking film “Lingua Franca,” which centers on an undocumented transgender Filipina living in Brooklyn and her struggle with identity, civil rights and immigration.

“Mercado Vicente felt strongly about sharing the film’s story with our community because we stand for Filipinx creatives whose voices are not normally heard in mainstream media,” Gonzales and Torres write. “We push for highlighting the experiences of marginalized voices in our community, especially those of queer folx and womxn.”

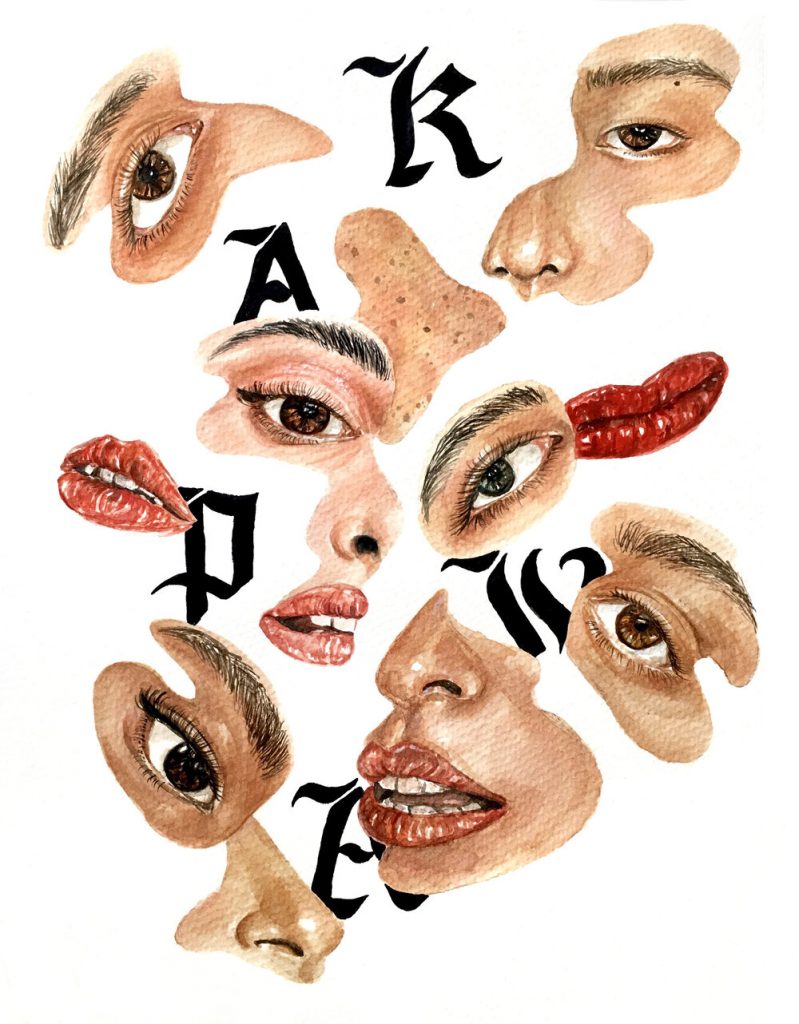

Much like every story published since the platform’s inception in July, the piece is accompanied by visuals exclusively created by Filipino artists for Mercado Vicente. For the feature on Sandoval’s full-length film, they’ve partnered with filmmaker Ava Duvernay’s production company Array Now that spotlights the work of people of color and women of all kinds.

There are nine artworks that interpret Sandoval’s masterpiece in that piece alone. But Gonzales is not stopping there. In a similar Instagram prompt that started “Stories”, he asks artists all over the world to share their interpretations of the film through art. The entries will then be uploaded to the index alongside the works of many other Filipino creatives.

‘Making sure that our stories are told’

So how does Gonzales manage all this creative output in the middle of a global shift due to the pandemic? Callouts are easy. With his over 3,000 Instagram followers and a community of like-minded Filipinos abroad, there is bound to be an abundance of material. It also helps that Gonzales’ peers in the Philippines—the likes of designer Carl Jan Cruz, his consultancy’s first client—help amplify this cause in the motherland. The problem really is how to go through the deluge of portfolios and submissions with his team.

“There is an extreme lack in the stories that are being told about being Filipino. The fact that we are a minority within a minority says something.”

“The plan initially is to put out two to three stories a week,” he says but that proved to be a challenge since they have to coordinate with the artists who are doing the visuals, too. Right now, he and his team are taking their time to sift through all of it and publish without pressure, which works well considering most of the writings are timeless.

Gonzales is banking on the vastness of Filipino experience, and it hasn’t failed him so far. He shares that right away submissions fit the prompt—he didn’t have to wring it out of them to create something that would click with Mercado Vicente’s goal: to give a platform to all kinds of Filipino voices around the world.

Maybe it’s the spare time we now collectively have in abundance in quarantine. But as Gonzales put it, it may also be that deep within, these stories have always been there but without an avenue to express them.

Despite 2020 being relatively a year of reckoning where we are now all recognizing the diversity of talent and experience, there is still a lot of representation missing in the mainstream media. “I think it’s why we’re pushing so hard for this one, too,” Gonzales says. “When they say Asian-American, they’re usually just talking about Chinese, Japanese and Korean people. What about the southeast Asian people?

“There is an extreme lack in the stories that are being told about being Filipino. The fact that we are a minority within a minority says something. The fact that even if you look at Hollywood and they say ‘Oh, we’re doing better with Asian representation.’ Yeah, but you’re only doing Eastern Asians. That’s what we’re trying to fight here: making sure that our stories are told.”

Before ending our conversation, 12 hours apart and with the internet connection testing us every 10 minutes, I ask what’s next for his ambitious project.

“We definitely want to look into music and film, it’s just a matter of us being able to build the website to host it properly. Just as there is no one way to be Filipino, there is no one way to be creative and there are so many creatives that call themselves multi-disciplinary and they are! It just shows you how talented Filipinos are.”

Header artworks by Venazir Martinez, Maura Rodriguez and Jill Arteche

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here.

Read more:

To know how Filipinos are coping in the pandemic, look at what they’re eating

For young readers, here’s an online library of Filipino children’s books you can access for free

There’s no one-size-fits-all-needs bike. Can these customizable Filipino-made wheels be it?