Augustine Paredes’ body of art explores queer desires along with the migrant experience in places where they are forbidden or simply overlooked

I first met multidisciplinary artist and photographer Augustine Paredes—in person, though we have been acquainted prior on Instagram—in the summer of 2022. He took a short vacation to the Philippines at that time, having been based in Dubai, United Arab Emirates since 2016.

We bonded over halo-halo and ginumis at a cafe in Makati where I almost didn’t get in for wearing a tank top (in summer!). Paredes came to my rescue and lent me his vivid blue chore coat.

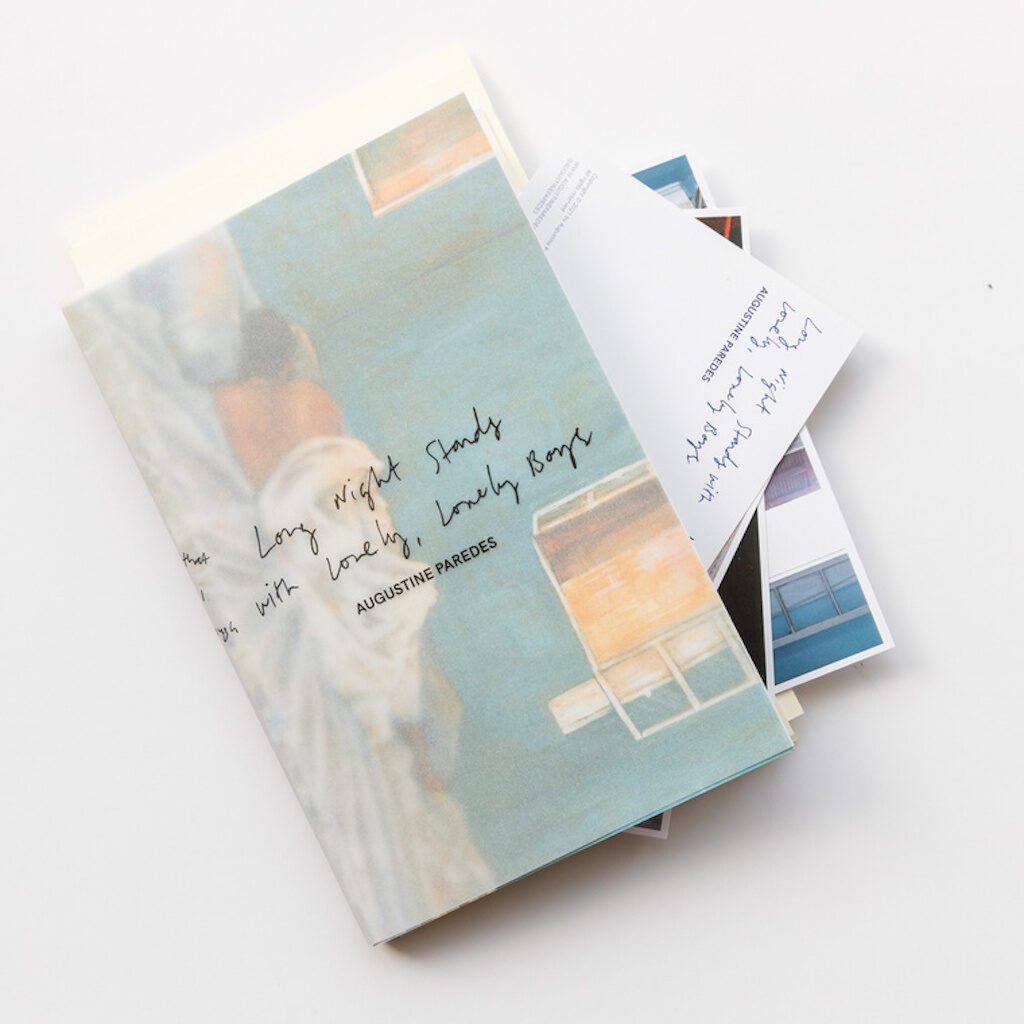

At 28, Paredes is a wisened soul, aware of the geopolitics of art and identity, having been born and raised in Mindanao prior to moving to the Middle East. It also helps that he is well-equipped with the tools to translate his experience. He writes, photographs, and even independently publishes books, including one called “Long Night Stands with Lonely, Lonely Boys.”

It being a book on his romantic, platonic relationships and “situationships” with other guys (but also ultimately in their absence, with himself), he had a hard time finding a printer in the land where homosexuality is criminalized.

Nonetheless, he made it happen.

Reading through it feels like being made privy to someone’s journal, to someone’s feelings, longings, and in turn to the lives of the people he met in the cities he went through. When he gave me a copy, I joked that it looks like contraband because it was packaged in a ZipLock bag, evidence that requires quick browsing, careful not to get caught—a feeling not foreign to queer people, who growing up had to hide their identities in stolen stares, stashed media, and bottled up emotions.

Here, there are things you can and cannot talk about in the most direct way, so every time I wanted to say something I would say it in a way that still respects the place that I am in.

It was first presented locally as part of the Manila-based gallery and creative production group Tarzeer Pictures’ 2019 Pride Month exhibition. The trio behind Tarzeer—Enzo Razon, Dinesh Mohnani, and Gio Panlilio—first encountered Paredes’ work online before offering to stock the book locally. They describe it as “a diaristic series blending artifacts from his daily life—vestiges of distances traveled and encounters had… an anthology of vignettes navigating feelings of intimacy, longing, loneliness, and love.”

When he is not busy documenting and creating art, Paredes works as a commercial photographer represented by Dubai-based agency Seeing Things.

Last November, his first international solo exhibition entitled “Paradise 4Ever” opened in Dubai under the Middle East-based photography gallery Gulf Photo Plus.

The exhibit, which was well-received particularly by Filipinos in Dubai, is an amalgamation of tenderness, he says. “It aims to retell the journey of a migrant body seeking paradise.”

“Paradise 4Ever” has recently been extended until Feb. 25. On the eve of this announcement, Nolisoli caught up with the multidisciplinary artist to discuss his roots, creative inclinations, artistic process, and future projects.

Hi Augustine! Congratulations on your first international solo exhibition and its extended run. To begin, why don’t you tell us about your life before you became an immigrant?

Before moving to Dubai, I was a very active member of our small artist community in Davao. My friends and I ran a now-defunct online magazine called LIEU Magazine, which championed new voices, local musicians, and artists in the city. Then in 2016, I moved to Manila to work as an art director at an agency.

What necessitated a move to Dubai?

An opportunity came to be an assistant photographer for a Filipino-owned studio, so I took that chance. I wanted to be exposed to the creative and art industry internationally, to absorb as much art and learnings as I could from the world.

Creative work has always been my means of getting by, no matter where I was because it is the only thing I know how to do.

You also traveled a lot for art fellowships and residencies. Has it always been your dream to go around the world?

When I was working in Davao as a photo editor for a Sweden-based company, I was sent to Stockholm for training. That was the first time I went to Europe. There, I felt a sense of freedom that I have been craving since. Growing up in many different cities in Mindanao brought upon this yearning for somewhere else.

I grew up moving a lot, so traveling and moving were almost part of my upbringing. I was born in Cagayan de Oro but every four years, I moved cities for education.

Growing up, is there a piece of work, an artist, or a movement,that inspired you to pursue the arts?

When I met Wawi Navarroza in 2015 at Thousandfold, she invited me to present a body of work and wanted a copy of a zine I made then. I was in awe of how much one could do with the camera. I have always aspired to be able to do what she was and is still doing. In all honesty, she was the first one that I looked up to as an artist who utilized the camera.

I have always loved Wong Kar-wai. Seeing “Happy Together” at 16 gave me so much inspiration and a yearning for that way of storytelling.

Then there is Ocean Vuong and Joan Didion. They have guided me throughout my journey with the written word.

How is your experience so far living in Dubai? What struggles does being an immigrant queer artist present in terms of your personal life and life as an artist? Do you find that in a foreign land, creative work is a means to get by unlike in the motherland or is it also equally financially precarious?

I like living in Dubai in all honesty. I’m lucky to have been part of the emerging creative community here.

Being a queer BIPOC artist everywhere is hard, you have to constantly prove your worth and fight for your space. Creative work has always been my means of getting by, no matter where I was because it is the only thing I know how to do. Wherever I am in the world, being an artist brings financial precarity; thus I always try to keep my day job as a commercial photographer.

Reading “Long Night Stand with Lonely, Lonely Boys,” there’s a kind of restraint that even though you outline what you see, what you feel, and what people say, you never really dive into what happens at the moment. A kind of self-preservation, if you may. Is that intentional or is that a consequence of having to publish your book in a conservative country?

Maybe it is self-censorship. In the 10 years that I’ve been practicing as an artist, I spent six years in Dubai. Here, there are things you can and cannot talk about in the most direct way, so every time I wanted to say something I would say it in a way that still respects the place that I am in. I always wanted to keep myself safe, especially the people around me. There is beauty in subtlety as you are able to say what you want to say and people who know will understand, and people who do not will not be angered.

I don’t know how to put it, but I think, there is a language only known and practiced by migrants and the diaspora.

You work with many kinds of media. I’m curious about your archiving process, especially with photos. And how do you manage to keep all those memories intact? Do you write at the moment or do you just have an amazing memory?

My memory is a blessing and a curse. I remember the little details. I can tell you, for example, that I lent you my jacket when we met the first time. Or the first time I kissed a boy was while “The Orphan” was on TV. Or the song “Sailing” by Christopher Cross, my dad’s favorite, played inside the bus in Stockholm when I was heading to the airport. And the photos help me remember. I write when I can and want to, in a way writing becomes a metaphorical salt on a wound.

You have actually exhibited in Manila. How did they happen? Are you actively seeking to show your work here? If so, how has the experience been being away and yet wanting to “telegraph” your experiences away from home?

The first time I exhibited in Manila, I was part of a group show in Thousandfold in 2016. That introduced me to photographers I look up to like Navarroza, Tammy David, Czar Kristoff, and AG De Mesa.

My last solo exhibition in the Philippines was held in [the now-defunct] Today X Future. It was titled “How Strangers Meet: A Visual Narrative of a One-Night Stand,” and it lasted for one night. I took the same exhibition home and put it in a toilet in Davao, the same night I left for Dubai.

In 2019, after being shown in Malaysia and Latvia, “Long Night Stands with Lonely, Lonely Boys” was shown at Tarzeer. I wasn’t able to go as I could not afford to.

It will always be a dream of mine to have a solo exhibit in the Philippines. I will always desire a space in the local art scene.

How do you manage many prolonged personal projects? How do you know which photos you’re taking is for one project or for another?

I’ve come to realize that all my projects are connected, every project references each other. For personal projects, especially those that are rooted in my lived experiences, it belongs to one archive that I revisit all the time.

For your latest exhibition “Paradise 4Ever,” what was your process like?

It took me a year and a half to produce this project, and it started with me looking at all the photographs I’ve taken since 2014. My initial idea was to open my closet, the place where I have been hiding before I started becoming vulnerable with my previous projects. It was an excavation of many, many things. And then from there, I started making new images out of the old ones by collaging and painting over them, and then I made entirely new images.

Site-specific multimedia installation

Acrylic on canvas, fabric, tarpaulin, metal

What’s next for you after “Paradise 4Ever”?

I’m going back to Al Ula, Saudi Arabia to exhibit “The Bitter Taste of Sweetness,” a series of paintings and a performance.

At the beginning of March, I’m moving to Frankfurt, Germany to study fine arts in Städelschule under the South Korean artist Haegue Yang. By then, I might be writing “Based between Frankfurt and Dubai” in my bio. Just kidding. Maybe.