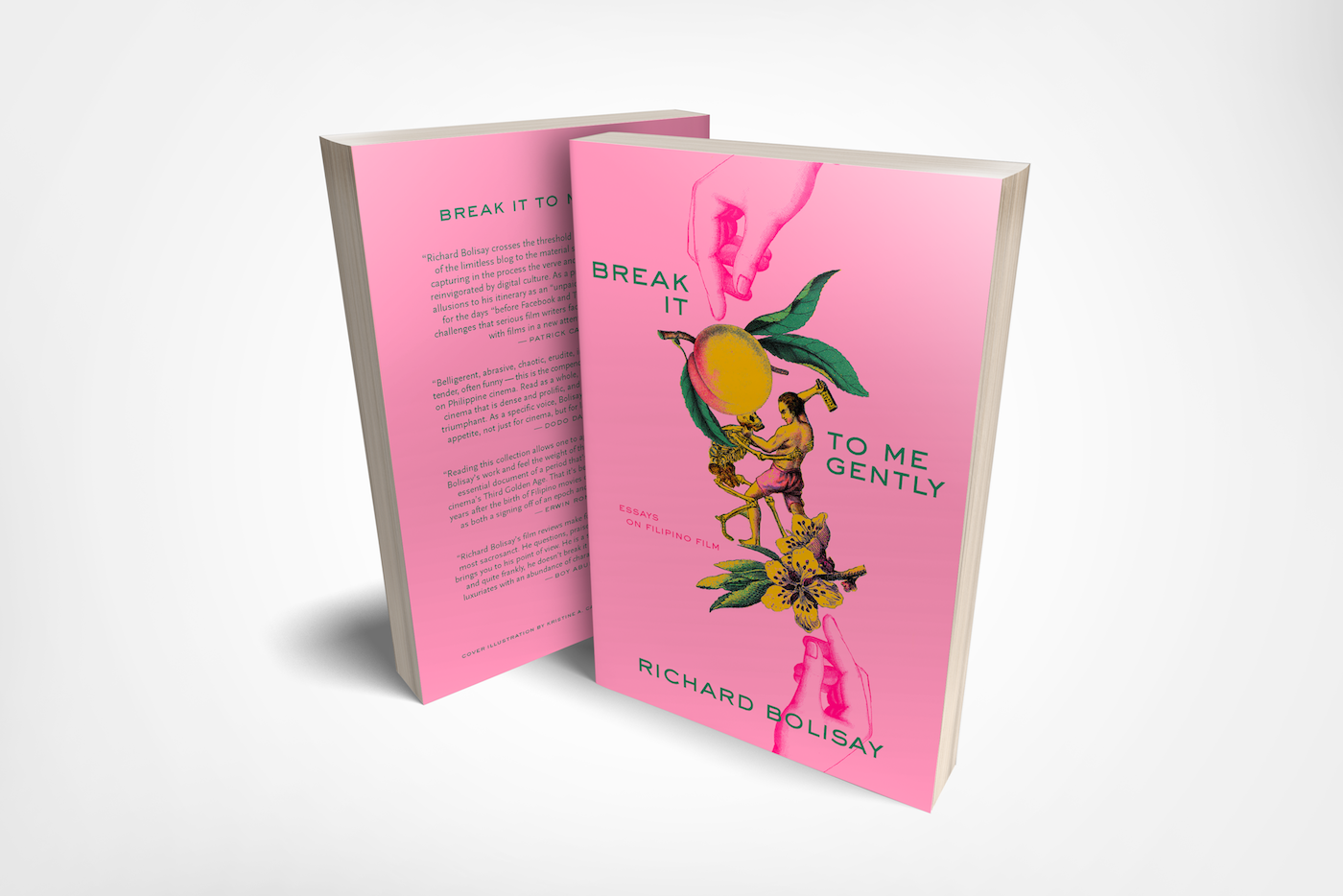

“Break It To Me Gently” by Richard Bolisay features critical essays about Philippine cinema

Being a film critic is one of the most challenging roles in the Philippines. You’re either overlooked, underappreciated, or slammed with, “then why don’t you make something better?” Worse, people would be oblivious of your existence at all. Film critic Richard Bolisay says it so: “There is a stigma to being a film critic, and one can easily notice the scarcity of people in the past and present who pursued it. Clearly, we don’t have a strong culture of film criticism.”

Read more: Nick Deocampo tells us why it’s difficult to preserve Filipino films

Even the love team culture affects film criticism; take it from what another film critic Philbert Dy said in a 2016 tweet: “If all we’re doing is arguing about which love team is better, or comparing box office receipts, we aren’t really talking about movies.” In “On Poetics and Practice of Film Criticism in the Philippines” by film professor Patrick Campos, he stated that film criticism is not only a “para-site of cinema” but also a “primary site of struggle and contestation for meaning and direction.” In Richard Bolisay’s new book, we already sense how difficult it is to write about cinema just by reading its title: “Break It To Me Gently: Essays on Filipino Film.”

Read more: 5 Filipino throwback films spearheading modern feminism

“[In] a country like the Philippines where criticism is not always welcome and will be taken personally, even when it is solely about the text—say, a film—we need to break things to people gently,” Bolisay explains after I asked the meaning behind his book’s title. “Of course whether or not I actually achieve this in my writing is not for me to say.”

“Break It To Me Gently” is a collection of critical essays on Filipino cinema. Expect stories woven through politics, history, journalism, and so much more, that can both champion and trump what we currently know. But just like any other critique about film, the book is more than that.

Hi, Richard! Can you tell us a bit about yourself and what you’re currently doing?

I teach film theory in the University of the Philippines. Outside of that day job, I’m preparing a national conference on alternative cinema with my friends in Cinema Is Incomplete, watching as many films as my time permits (just saw the latest film by James Gray titled “Ad Astra”—lovely, magical, devastating), and figuring out what the next book will be. Also: refreshing Twitter as I write this.

When did you start writing essays about film? What made you pursue it?

I started writing about film on my blog, “Lilok Pelikula,” before Facebook and microblogging took over our lives. This was the time when the local independent film scene was growing and becoming more and more exciting, with loads of new films and filmmakers coming out, new spaces and new horizons to pursue. This was in the mid-2000s. I wrote about cinema on that blog for 10 years, from 2007 to 2017. Obviously I was watching films long before that, happy with whatever I could get access beyond the mainstream offerings. In the course of writing for the blog, which was really unpaid work, I became part of a community of film enthusiasts and a small group of film critics, and later on received invitations to cover or become part of the jury for film festivals, here and abroad.

Totally grateful to the UP Film Institute Director Patrick Campos, critic and filmmaker Dodo Dayao, writer and editor Erwin Romulo, and Boy Abunda (who needs no modifier) for reading my book and providing these generous blurbs. Pre-order it here ??https://t.co/5HiROj2FJb pic.twitter.com/pS9QnWczVG

— Richard Bolisay (@richardbolisay) September 25, 2019

Can you clue us in on your book? What areas are you covering?

The book contains selected writings from “Lilok Pelikula,” envisioned as a whole to provide the reader with the breadth and scope of the cinematic creativity across independent and mainstream cinema of the time. So this is a book of critical essays on film, a record of my active years as a film critic, and while we are wary of periodization, we accept that the easiest way to provide the reader with a sense of what’s covered in the book is to peg it to certain films: from the 1984 Ishmael Bernal-Amado Lacuesta collaboration “Working Girls” to 2017’s “Respeto.”

Read more: Instead of two MMFFs, why not uplift quality films?

Can you tell us about the team behind this book?

When QCinema Film Festival agreed to fund this book, the next step for me was to figure out how to come out with an actual book given that I knew absolutely nothing about it. I just knew I needed funding, given the kind of first book I wanted to come out with. I knew I wanted to have control over what the book would contain and what it would look like, but I wanted to be able to leave the rest of it up to someone else. Everything’s Fine is a small press set up by the poet Oliver Ortega and the critic Katrina Stuart Santiago, and it appealed to me that they sought to make sure not only that we release a book I could be proud of but also that I be compensated for it, enough to be able to write a second book. They were the ones who got Kristine Caguiat to do the cover art for the book, and who have walked me through this creative process.

If you could only watch three Filipino films over and over for the rest of your life, what would they be?

If I had to watch something over and over, they have to be incredibly funny, right? “Salawahan,” directed by Ishmael Bernal. “Booba,” directed by Joyce Bernal. “Tanging Ina,” directed by Wenn Deramas.

What is your advice to young people who’d like to try film writing as a hobby or career?

Go out and watch films on the big screen. Be resourceful. Look for those films that cannot be screened here in any way. Watch them. Be voracious. Start writing. Write, write, write. Revise, revise, revise. Revise till the very end. Then let people read it.

Read more: We now have a film archive kiosk and it looks pretty cool

In its 100th year, what do you think Philippine cinema needs right now?

We need better institutions that actually seek to protect our film workers, those that are clearly on the side of the small and independent film. We need initiatives that develop and educate film audiences, managed by people with integrity and experience who do not blatantly feed us with the false and dangerous belief that the measure of a good film is how long it stays in cinemas. We need to reassess and redefine our measures of success, and how these things matter to us, as filmmakers and filmgoers who care for Filipino creativity. We need more critics. We need more readers. We need more readers who will encourage critics to pursue writing. We need actual critics, not PR machines. We need the critics to make a living out of what they’re doing.