In most articles and biographies, National Artists of the country are often talked about hand in hand with their work, projects, achievements, and advocacies. It is very seldom that stories would dive into the lives they live outside their occupation since what they do in their jobs are already too interesting not to be missed—enough to fill more than a thousand words in an article.

However, it is also important that we recognize these esteemed Filipinos that like any other citizen in the country, they gave so much value to their families, too.

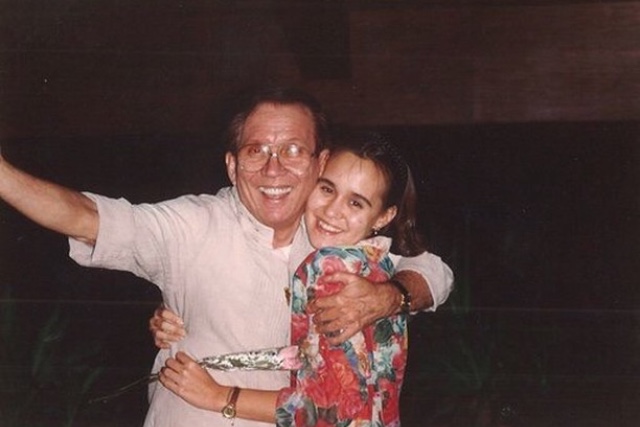

We’re shifting our focus to that aspect of our artists this Father’s Day. Beyond the design, paintings, buildings, and styles they have created that will surely be known for many, many generations, fathers Francisco “Bobby” Mañosa and Carlos “Botong” Francisco have also left their families incomparable memories and maxims their children and grandchildren continues to uphold up to this day.

The magical Bobby Mañosa

For a lot people, Mañosa was a lot of things: a National Artist for Architecture, a toy designer, a furniture designer, a musician, and the pioneer of many architectural forms. But in the eyes of eldest and only daughter Bambi, who saw him above these titles, all these characteristics can be summed into her father’s one trait—magical.

“Everything he did was magical,” she said in a phone interview with Nolisoli.ph. “I would say I had a very different childhood because of him; because of his magic. Every day with him was special.”

Bambi recalled that Mañosa, as a man of the creative field, would always make sure to make everything fun. “He liked playing,” she said. “At restaurant nowadays, you would see children stuck on their iPads. When I was a child, he would invent games on the spot or make something fun out of what’s available.”

He always made sure to be at the helm of milestones in the lives of his children, too. On Bambi’s first birthday, a time when there were no event planners, Mañosa did everything—from the invitation design and party decorations to games and furniture. “He even dressed up as the clown! He was always like that, curating everything he can imagine.”

With her father’s impressive creativity, Bambi said being bored in the Mañosa household is a sin. “The word bored is for people without creative minds,” Mañosa would utter to his children. He encouraged them to always give time for imagination and fun.

And that includes even when he takes them to work.

Site visits in the eyes of a child

“He won’t let us just sit on one side and wait for him. He would always make us feel part of the process,” Bambi said. For example, if Mañosa is setting up a new project, he explain every step of the way for the children. He would then encourage them to help out by getting a certain tool or designing a specific spot. “I remember that when I was a bit older and he was designing this small carnival in Alabang, he would make me do things like design the souvenir shop for him. He enjoyed his work a lot so he made it enjoyable for all of us.”

(READ: EDSA shrine now an important cultural property)

Mañosa also made site visits like a trip to the amusement park. “One time, when we were on our way to a site of a construction area, he narrated all the things we should expect—but in his incomparable, magical way. ‘We’re going to a big mountain with lots of trees and hills where you can slide down,’ he would say when in reality, it would just be a big pile of dirt with a bulldozer on one side. He just knew how to excite us.”

Sometimes he would take little breaks from work to play. When he was designing the old Nielson Tower, where restaurant Blackbird now stands, Mañosa tagged his children along and would challenge them in small games for a few minutes, like a race up a flight of stairs.

‘Never a dull moment’

When the electricity is down in their house, Bambi recalled that her father would take them outside with chalks and teach them to “trace their shadows.” He would then color and make costumes for their “shadows” with them. “There was never a dull moment with him.”

Mañosa might never had brought home his work (he won’t talk about business at home either, Bambi said), but he made sure to bring the talent he uses in establishing impressive and magnificent buildings everywhere. Even without the architectural esteem, Mañosa was, all in all, an amazing person.

As Bambi said, “He turned the mundane, ordinary things to extraordinary things. How can a child not be drawn to magic like that?”

Botong Francisco, devoted artist and father

When Nolisoli.ph went around Rizal in March, we realized that it’s almost impossible not to recall the great National Artist for Painting who grew up in the area. If not his works, his name would pop up everywhere—from the Balaw Balaw Restaurant to the Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs.

(READ: Where to eat and go in Rizal: A day-long tour)

The muralist’s grandson Carlos “Totong” Francisco II, who is also an artist himself, shares the same respect the people of Rizal give to his grandfather. Although he was not able to grow up with him around, he makes sure that everything his lolo did is preserved and accessible by everyone.

“I was not able to grow up with him, pero lumaki naman akong surrounded by the people who knew him the most kaya parang nakilala ko na rin si lolo,” he said in March.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half][one_half_last padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

An artist at all hours

Francisco was remembered to be usually locked up in his studio. “Kapag nagpi-pinta naman daw siya ng murals, lumalabas daw si lolo tapos sa tabing-ilog magpi-pinta.”

However, he might have devoted all his time to his art, but he made sure that his family understood what he was doing for the field and the country.

In an exhibit into his life that was mounted by the Yuchengco Museum in 2013, Francisco was revealed to be a caring father who frequently sent letters to his eldest daughter Carmen, who was then studying and working in America.

In one of the letters, Francisco explained to Carmen the kind of power art beholds. “Art to live must go back to a bigger audience,” he wrote in the exhibited document dated Mar. 5, 1968. “For this is it must have the power to communicate and not to repel.

That is why I love to paint big murals, for like a composer I can create a symphony from the history of our country our own way of life.”

Francisco and his studio might have been inseparable, but that doesn’t mean Francisco was distant. He remained close for his family to understand, care, love, support, and respect him both as a devoted Filipino artist and a devoted Filipino father.

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our weekly newsletter here.

Read more:

National Artist for Architecture Francisco Mañosa has passed away at 88

Spot the National Artist: Where the BenCab and Ocampo works are in this year’s Art Fair

National Museum now displays Jose P. Alcantara’s 50-feet relief sculpture

Read more by Amierielle Anne Bulan:

How Francisca Reyes-Aquino sought and fought for our country’s folk dances

Why it’s important to view art to understand than to critique