When you’ve got no less than Channing Tatum and Chris Pratt calling for “equal opportunity objectification,” the viral sensation that is “Hot Pulubi” seems to have been inevitable. Empowerment is preached as the outcome of watching other women being staged-humped by the glistening beefcakes of Magic Mike XXL. Though I wouldn’t go that far, I’d say there’s a cultural achievement in women and gay men finally enjoying the same permission to perv in both mainstream and alternative media.

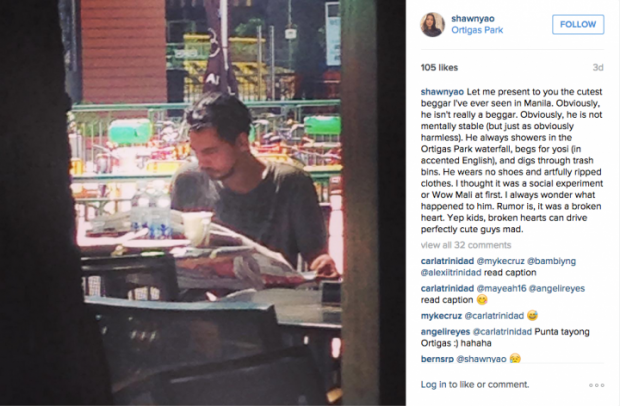

Today, the latest male body on display in Filipino social media is “the Hot Pulubi of Ortigas”—first captured by TV5 host Shawn Yao on her Instagram, but made viral by the website When In Manila, where the story has been shared almost 2,000 times. This also follows the site’s many other engineered #thirsttrap sensations, such as the hot doctor of St Luke’s hospital and the hot professor in Bulacan.

When I first saw the picture of this unshaven, tisoy man reading a newspaper, my first reaction was, “Why is this even a story? This guy isn’t even hot!” The second reaction was, “God, my 60 year-old mom could have taken a better picture!” as the grainy zoom-in and shadowy lighting weren’t even flattering.

Neither hot nor really beggar-looking in this picture, why is he newsworthy then?

White love

Reading Shawn Yao’s caption of her photo and the flood of comments that followed, the hype and discussion reveal the class divides in our society. We see the ways in which we choose to either care for or ignore the poor based on judgments of their bodily appearance.

Many comments fixated on this Keanu Reeves-lookalike for looking pleasantly different from ordinary (read: unworthy) beggars. As Shawn suggests, he’s “obviously not really a beggar.” She could tell from his Western English, hygiene practices (“showers in the Ortigas Park waterfall”) and clothing (“wears artfully ripped clothes”).

The imperative to care for the “hot pulubi” is triggered not by middle-class compassion for really-poor others, but by how he belongs to “our” world. “He’s not really a beggar,” suggests Shawn and other commenters, who see him instead as “one of us” though astray from the righteous path the middle-class traverses. It’s interesting that many commenters related to his seeming heartbrokenness, as if heartbreak is an affliction that the truly underprivileged can’t afford. Knowing they’re vulnerable humans like us, it’s the only time we become charitable for them.

In our society where the poor participants of game shows are demonized as “lazy” for winning money by “being there and doing nothing,” it’s curious to find many online commentators expressing exceptional care for the “hot pulubi” because of his ethnicity. When we ignore the reported fact that he refuses alms no lower than P50, what makes him any different from the persistent parking boys who ask for coins not food?

Simple: he’s white. And our white love sparked pity and care for him for being in a “strange and foreign” land.

A test of compassion

This month, Filipinos made global headlines for the success (and dangers) of using social media in fundraising for a poor, young boy photographed studying outside a McDonald’s. The young boy was deserving of attention and care because of his hard work as captured by one photograph. Today, “hot pulubi” is made viral because of his exceptional physical attributes.

The issue here is how and why we make individual stories of poor people more visible than most others. For every “viral” handful that appear sincere and trustworthy, there are many others ignored, or even locked up for being “eyesores,” such as during the Papal visit in January.

For me, the real test of middle-class compassion is whether we can learn to be most charitable to those who resemble us least rather than those who appear to embody qualities we quite like to see in ourselves.

Jonathan C. Ong is the author of the new book, The Poverty of Television: The Mediation of Suffering in Class-Divided Philippines.