This story was originally published on Sept. 21, 2018

This is how the Marcoses used myth for deceit

Nagsimula ang daigdig nang lumitaw si Malakas at si Maganda mula sa nabiyak na puno ng kawayan. This Philippine legend, that has been handed over from generations to generations, has no specific author or structure thus it’s been written and rewritten many times for Filipino textbooks. “Ang Alamat nina Malakas at Maganda” remains as the country’s own myth of the origin of human life, a different take on the story of creation from the Bible’s Book of Genesis. But during the Marcos Martial Law era, even this unpretentious folklore was taken advantage of.

Late dictator President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his wife, Imelda, saw the chance to fashion themselves in the images of Malakas and Maganda, who both embody unique and true traits of a Filipino man and woman physically and emotionally. This led the couple to commission local and international painters to depict them.

Ferdinand was Malakas (the strong one) and Imelda was Maganda (the beautiful one). As glaring as it is, the myth-making is the couple’s obvious attempt to hide their intense and selfish desire for power and wealth. It was their way to achieve “mythic legitimacy for 1970s authoritarianism,” as mentioned by educators Pia Arboleda and Peter Cuasay in a book on folklore and folklife.

They tried to represent themselves as “origins” of the “New Society” that Ferdinand always talks about in his speeches. History professor Vicente Rafael said in his study that “Mrs. Marcos liked to think of President Marcos and herself in terms of these legendary First Filipinos.”

“As Malakas and Maganda, Ferdinand and Imelda imaged themselves not only as the ‘Father and Mother’ of an extended Filipino family,” Rafael wrote. “They could also conceive for their privileged position as allowing them to cross and redraw all boundaries, social, political, and cultural.”

Inquirer columnist Ma. Ceres Doyo said in her 2013 opinion piece that the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda used the myth to soften the “portrayal of their likenesses in art that drew from myths and legends.”

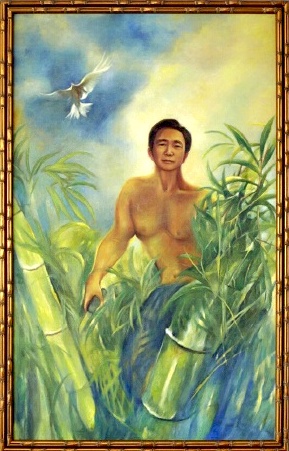

One of the most controversial paintings of Ferdinand as Malakas showed a half-naked, muscular young man coming out of a bamboo field. The figure of Ferdinand carried a gentle expression, dreamy even. Seen on the skyline behind him is a white dove, which is considered as a messenger of peace and love in most cultures. Each trait of the painting—from the posture to the bright colors—add to the almost utopian atmosphere elicited by the art piece, which is exactly the opposite of the despotic regime under the Marcoses.

Artworks featuring Imelda, on the other hand, is mostly embodied in very feminine settings. In one of her portraits as Maganda, Imelda is clad in a white and translucent flowing dress while her figure steps out of a bamboo tree. Her long dark hair is blown by the wind. A rainbow appeared above her while red flowers bloomed below her.

Both showing details dipped in impressionism, the mentioned paintings were done by the late Evan Cosayco. These were displayed at the Malacañang Palace museum, as told by artist Pio Abad in an interview with Inquirer.net.

There were other commissioned portraits of the couple from local and international artists. News in 2016 gave light to a painting of Ferdinand as Malakas, but clad in a fatigue. The art piece by folk muralist Jose Blanco was displayed in a local government office in Quezon City.

There also was an attempt to rewrite the legend that culminated in the celebration of the Marcos regime, Rafael noted. It’s clear that they wanted their own respectable myth in a bid to cover their large attempts to fabricate history.

To strengthen their image as patrons of the art, Ferdinand and Imelda also pioneered cultural projects that varied from architecture (Read: Looks like the Marcoses were Brutalists by choice) to literature. “The Marcoses deployed a cultural repertoire that ranged from narratives of virility and romance to spectacles of nationalist vigor and feminine allure, appearing to evoke change while simultaneously eschewing the imperatives of social reform,” Rafael said.

With this and the crackdown of media organizations critical of the government, it’s true what journalist Primitivo Mijares wrote in his tell-all book “The Conjugal Dictatorship,” the 1970s Martial Law was an “era of thought control.”

And ripples from that era can still be felt today. With their almost a decade of take over of art, architecture, literature, and even the media (which has spread to the its new platform, digital), it’s not surprising how historical revisionism is still rampant at this age. Many people have fallen for propaganda. But many are also awakened. As we commemorate the 46th anniversary of the 1972 Martial Law on Sept. 23, may we continue awakening our fellow Filipinos from the effects of the myth-making and cover-ups the Marcoses attempted.