More than the total destruction of Marawi City by pro-ISIS terrorist groups, the largest handicap is its citizens. As of July 31, as many as 359,680 persons, according to the government, have been displaced because of the conflict. Out of this number, only four percent are in evacuation centers managed by the government in neighboring municipalities while most are in community-based and home-based evacuation centers throughout a number of nearby regions.

In the outskirts of Iligan City, hundreds are finding temporary refuge at the Buru-un Evacuation Center. The United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been providing immediate response to the need of refugees in evacuation centers like these. UNHCR advocate and member Atom Araullo visits these families to grasp a better understanding of the situation at these camps.

The real cost of displacement

It’s been two months since the Marawi crisis exploded at full force. While Mindanao is placed under martial law, refugees are concerned with their survival. UNCHR has been allocating tarpaulins, plastic sheets, blankets, and other core relief items to internally displaced persons. But these aren’t enough.

“We’ve been here for two months, but we are still not used to living in an evacuation center. My grandchildren, for example, have gotten sick already. We still long for home, no matter how humble ours was. We wait for the day we will have peace in Marawi again,” says Moreg Sarakan, a resident at the Buru-un evacuation center.

“When we fled Marawi, we left everything behind. Back in Marawi, my husband earns our daily keep as a laborer. Without any source of income here, we can only rely on the relief goods handed to us. Having jobs give us dignity,” says Janisa, a refugee at an evacuation camp in the Balo-i municipality of Lanao del Norte.

Harrowing narratives

Despite her age, Moreg Sarakan was forced to walk from Marawi to Iligan, about 40 kilometers away, to escape the fighting. She is already 100 years old. Fatima Lumabao tells her own tale. A mother of eight, four of her children went missing two months ago when they fled Marawi. “I cry every night wondering where my children are. One of them is just a 10-year-old boy, and sometimes I dream of him calling my name for help.” She adds that she’s found new friends who care and relate, helping her cope with the despair somehow. These stories have become commonplace among the hundreds of refugees in these evacuation camps.

Regaining a semblance of normalcy and hope

One way the refugees are trying to regain normalcy is by hosting weekly Sunday school. At a Madrasah (Arabic school) in Iligan City that was converted into an evacuation camp, the classes offer a form of relief, especially to the children. The owner of the Madrasah, 59-year-old Ustadz Adbulkarim Ambor, admits using his own limited resources to convert and manage the school-turned-evacuation camp. It’s the sacrifice of people like these that keep these communities ripe with the will to survive.

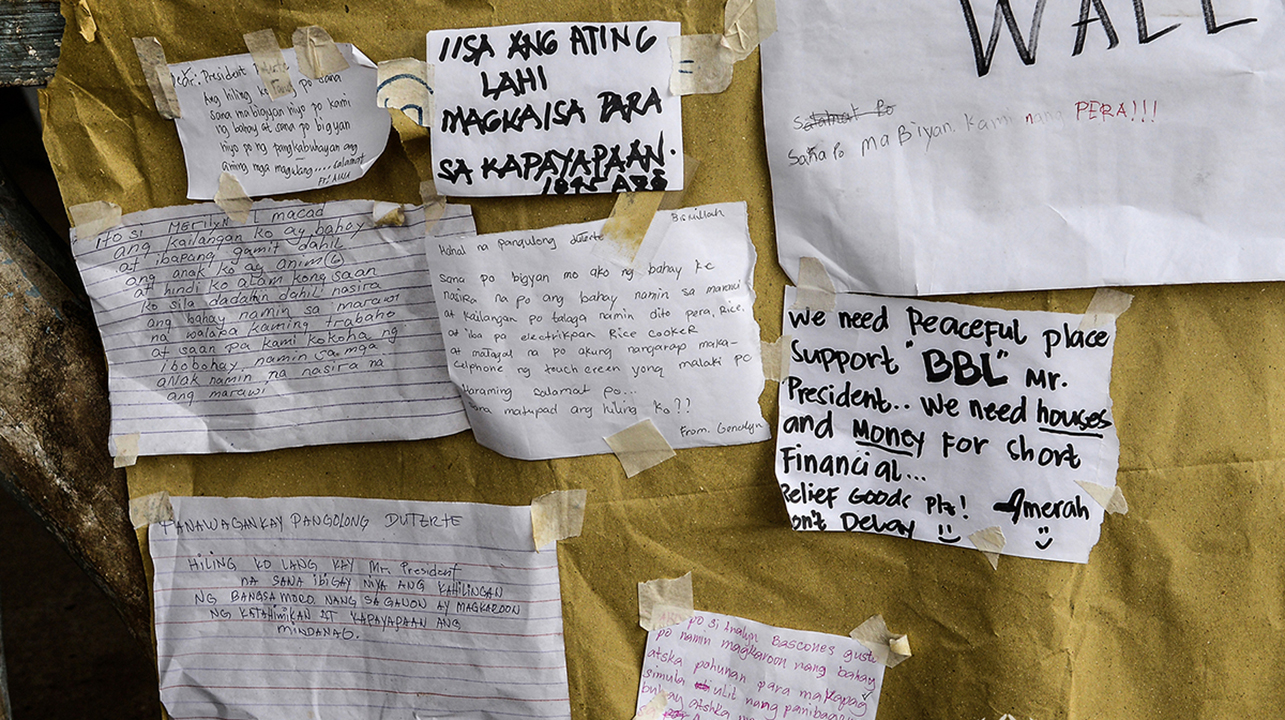

Back at the Buru-un evacuation center, families post hand-written notes addressed to President Rodrigo Duterte. These messages are filled with their hopes and dreams to rebuild their lives, find a safe place to finally call home, and ultimately attain peace in Mindanao.

Photos courtesy of UNCHR

Read more:

Your piggy bank can help feed thousands of children in Marawi

Beyond the fighting: What the Marawi crisis could also entail

Art and humor are saving soldiers in Marawi