The historic streets of Escolta, a once-thriving district of the glitzy 1920s to ’60s, is experiencing a kind of renaissance. A large part of this can be attributed to the younger generation’s revived interest in the old haunts of their grandparents’ youth; it’s not a coincidence that heritage conservation also experienced a resurgence when millennials eventually had buying power.

“Young artists are skipping Manila’s more mainstream galleries to exhibit on the street. A collective of visual artists holds a seasonal flea market there. Historic preservationists, too, are rallying on social media to revitalize the fallen business district, which feels a bit like a time warp, with fine examples of Art Deco, Beaux-Arts and neo-Classical architecture,” wrote Al Gerard De La Cruz about Escolta for The New York Times in 2016.

A sort-of flagship event for this revival was the Escolta Block Party, a quarterly one-day gathering to celebrate the thoroughfare. “When the tenants of First United Building along Escolta don’t focus on their day job, they throw one of the best parties in the city. Every now and then they throw a big shebang that literally runs the whole block for an evening, right after a series of talks, fashion shows, film screenings, and many other activities. It makes for a good night,” wrote our friends over at Scout two years ago. This year, the party has been beefed up into a month-long festival, with the inaugural Escolta Block Festival taking place this whole November.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half][one_half_last padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

One of the highlights that marked the festival was the unveiling of Escolta Exchange, a new creative hub, exhibit area, and incubation space located in a formerly abandoned space at the Panpisco Building—an artifact of the street’s heyday. It was created in collaboration with the festival’s organizers, the Manila Creative Exchange, and San Miguel Beer, which provided the festival’s boozy atmosphere. “The space was conceived as a way to show how some of the spaces in the street could be activated and used to enliven the street once more,” says Reymart Cerin, director of Escolta Block Festival.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

If you visit it midday, the space has all the staples of a café: coffee, cakes, and good, crumbly cookies the size of your palm. Basically, food fit for working on a paper or listening in on an informative lecture. Which, well, was pretty much what I did when I visited the place.

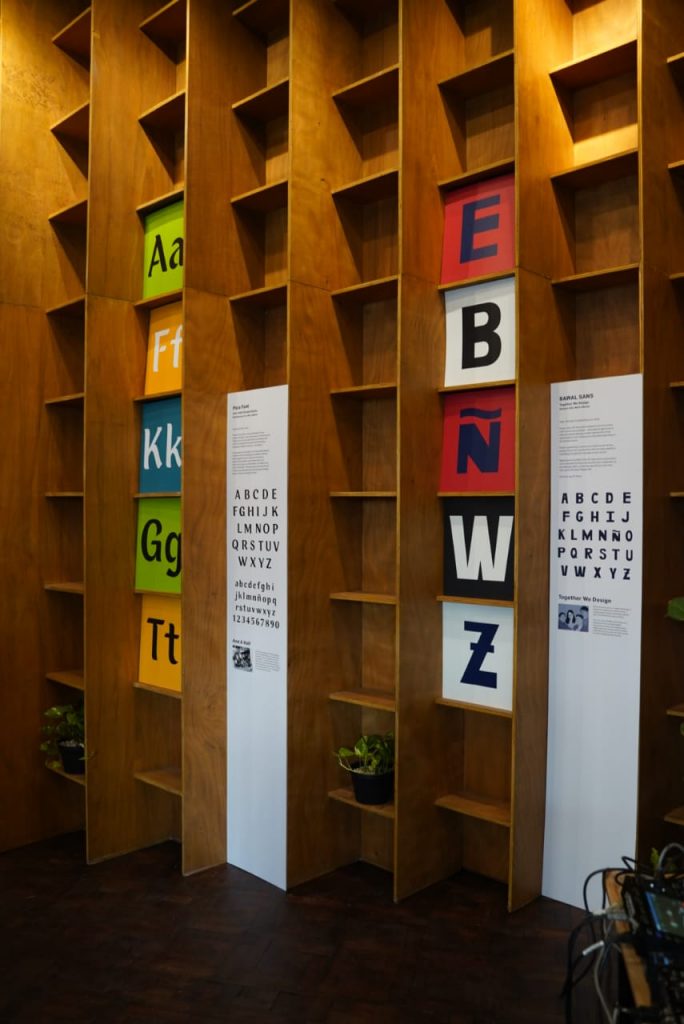

When I dropped by on Nov. 23, it was to check out its first exhibit, “Tipong Filipino: A Typography Exhibit,” and to catch up on a talk by the designers featured in it. Organized by Vince Africa and Clara Cayosa, “Tipong Filipino” gathered studios from around the country to create fonts that communicate the Filipino visual identity. “The design works are all inspired by how cities and communities function,” the exhibit’s description reads. As such, many of the fonts deal with topics like mass transportation and the struggle of a daily commute, but other fonts traversed a different route, like the woven-like Inandan from Cagayan de Oro-based studio Uncurated Studio, which takes its inspiration from nearby ethnic communities (I see you, Northern Mindanao representation).

“Just because it’s local doesn’t mean it’s low quality,” said Aaron Amar. He’s the graphic designer behind the typefaces Cubao Free, Quiapo, and Dangwa, all inspired by signs found on the streets and jeeps of Manila. Nikki Solinap, designer for Works of the Heart, shared the same sentiment, adding that, “Minsan naiinggit tayo from other countries” when it comes to having a design or visual identity. However, she points out that being able to feel that jealousy is a privilege of its own—the country “has more pressing problems.”

The designers all plan to publicly release the fonts for download eventually, but they’ll be taking time to sort out the kinks and refine them. Amar’s Cubao Free, however, was already released last year.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half][one_half_last padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

When the panel ended and the day moved on to night, the space itself also transformed: chairs were moved, a projector replaced by a DJ booth, and bottles of beer showing up on the countertop. As a multipurpose venue, Escolta Exchange isn’t just a place for talks and exhbits—it’s also where people can unwind at night, maybe drink with their friends. This being a space created in part by San Miguel Beer, at night, an Escudo (the brand’s mark) is also projected onto the ceiling.

Get more stories like this by subscribing to our newsletter here.

Read more:

Cartoons as propaganda: How two animated films in 2019 dealt with history

Gina Apostol is not in the business of making people feel comfortable

The 2019 #SEAGamesFail is an accurate depiction of Filipino hospitality