In 2016, the country for the first time joined the prestigious Venice Biennale of Architecture, and after months of waiting, the Philippine Pavilion titled “Muhon: Traces of an Adolescent City” is finally home. You can catch it at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila until Dec. 29.

According to Sen. Loren Legarda, whose office spearheaded the Philippines’ participation in the Venice Architecture Biennale with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Department of Foreign Affairs, our presence at the Venice Biennale “is one way of conversing with other nations.”

True, this participation ultimately catapults the country into the global architectural scene and is indeed, a form of “cultural diplomacy,” as the senator put it, but it also efficiently raises the question, “What does Manila mean to you?” Metro Manila, after all, is synonymous with the Philippines in many ways. As a Filipino, Manila should mean more to you than hellish traffic and streets that reek of piss.

“The city is a narrative of your story as a people, as a society. In way, it reflects the collective ideas and aspirations,” said Juan Paolo de la Cruz, one of the three members of Muhon’s curatorial team. The other two are Sudarshan Khadka, Jr. and Leandro Locsin, Jr.

The word muhon roughly translates to monument or place-marker, which, as it turns out, has been a topic of debate ever since the Torre de Manila issue blew up first in 2012 and again in 2015. For those who need reminding, the Torre de Manila high-rise was dubbed the national photobomber after people realized it would mar the Rizal Park skyline. After that, the sale or demolition of several heritage structures added to the heat.

“If we keep tearing out entire chapters, it becomes a disjointed and disconnected narrative. Generations to come will have nothing to look back to and nothing to anchor on,” de la Cruz added.

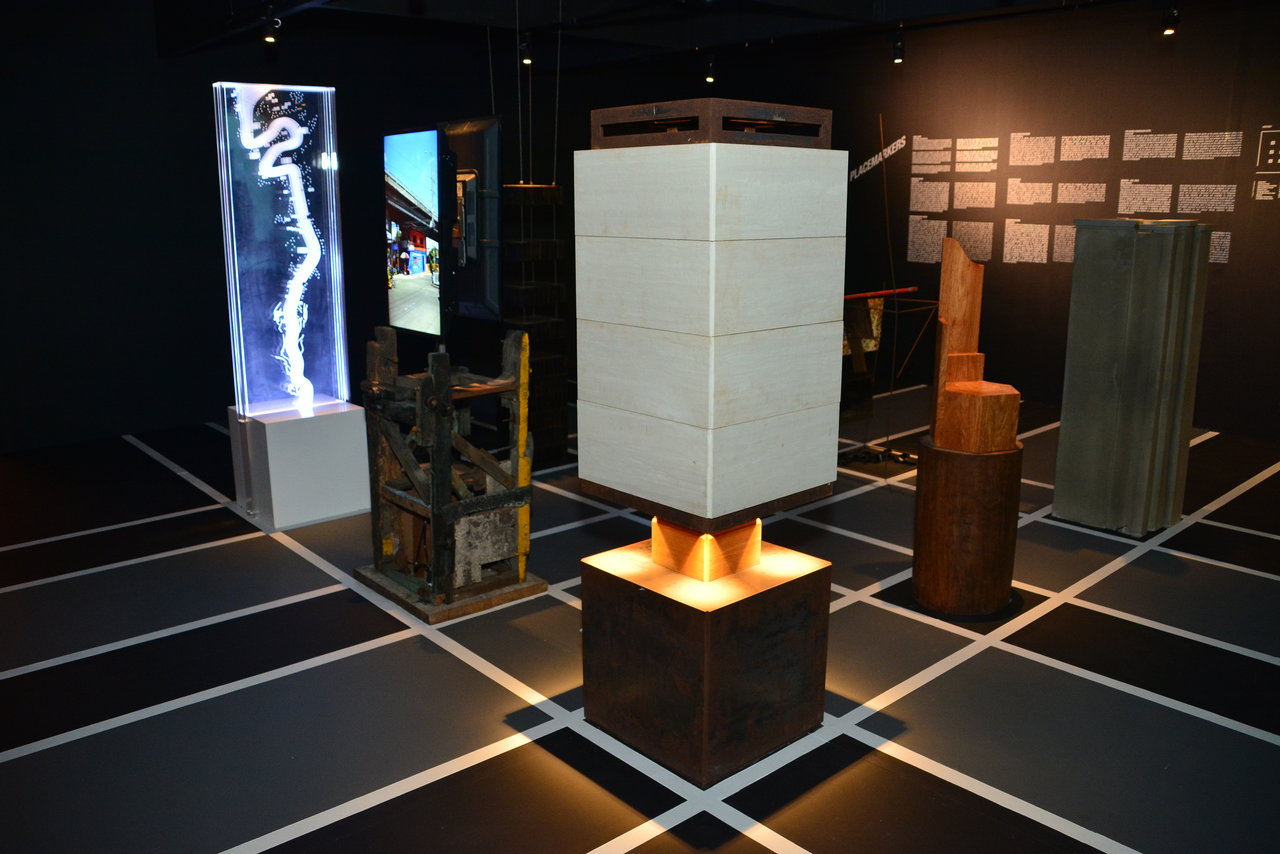

This is where Muhon comes in. The homecoming exhibition is a visual dialogue on progress and permanence rooted in identity brought about by heritage. These concepts are not new, but remain vague in the context of Metro Manila as a megalopolis in its “adolescent” stage, which is somewhat characterized by an endless, ruthless cycle that ping-pongs between two stages: destruction and rapid creation.

Can progress go hand in hand with the protection of heritage in mind? Does the conservation of old structures hinder infrastructure growth? Does the general disregard for heritage structures reflect the Filipino’s lack of identity? These are just a few questions that Muhon brings to mind by investigating and deconstructing nine of Manila’s many identifying markers.

All markers included in Muhon are 40- to 50- years-old post-war buildings and urban features, which were chosen by nine participants—six architects and architectural firms, and three artists—as the subject of their creative analysis.

The Philippine Pavilion transports you to:

- Pasig River (CIS Design Consutancy)

- Pandacan Bridge (Tad Ermitaño)

- Ramon Magsaysay Building (Design Studio Co.)

- Makati Stock Exchange (LIMA Architecture)

- Kilometer Zero (Poklong Anading)

- Tahanang Pilipino (Mañosa and Co. Inc.)

- The Manila Mandarin Hotel (Jorge Yulo;)

- Binondo (Mark Salvatus)

- Philippine International Convention Center (Ed Calma)

Each place had three interpretations—one for every room in the Pavilion, namely History, Modernity, and Conjecture. Much like a gradient, the rooms are easily identified through the amount of light that fills them. History, the darkest of the three rooms, envelops audiences in a quiet mystique that urges them to look through memories, while its polar opposite, Conjecture, is bathed in white light, opening up the space; an allusion to endless possibilities and boundlessness. Modernity is visually the grey area in between and represents the city’s current state. The three rooms can also be seen as a timeline of Manila.

The participating artists, architects, and architectural firms were chosen on the basis of cultural contributions, and social and urban commentary in their current work.

“Not too long ago, maybe three decades ago, artists were talking to architects, and musicians and dancers, and a lot of really good things were produced. That was normal then. Somehow that all disappeared,” said Locsin, Jr., who recalled a time when his father looked to his friends from the arts and literary scene for effective collaborations in design. “People kind of defaulted into their own groups and the conversation stopped. This is a very conscious attempt to try and restart that whole thing.”

Muhon indeed restarts this conversation between competitors, between people with contrasting interests and views, between those in varying fields. The urban assemblage of Manila isn’t only a representative of spaces and structures, it also stands for people and the harmonious merging of diverse ideologies.

“Folks who are in positions of influence have the responsibility to be inclusive when it comes to development. We hope that businessmen and the country’s leaders talk to anthropologists, to cultural workers, to scientists, writers, artists. There is room for everyone,” he added.

And maybe, just maybe, this conversation turns into genuine concern, and eventually, newfound love for our city. Because at the end of the day, Manila is very much part and parcel of our country. Its situation will always reflect that of our own, and escaping its grime and grit is escaping your identity.

[one_half padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last padding=”0 5px 0 5px”]

[/one_half_last]

“We’re still in the process of searching [for our identity]. But I feel like the idea of searching is actually more important than the finding part. This exhibition starts this conversation, of people thinking about these things, of searching for a sense of identity,” noted Khadka, Jr.

Read more:

Local heritage sites are being restored by this unlikely group of youngsters

Remembering the Manila Metropolitan Theater

Four heritage sites that need to pull a Met

The last wooden Art Deco school in Binondo was demolished

A photographer took aerial photos of Manila and they’re utterly suffocating

This is why the world thinks Manila is the worst place in Southeast Asia

Stop whining about Manila being one of the world’s most stressful cities

Photos courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila