Emerging as 2nd Best Picture and bagging several awards from the Metro Manila Film Festival’s Gabi ng Parangal, “Gomburza” is proof that history is not an outdated subject

“Gomburza,” the 2023 Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF) entry centered on the lives of the three martyred priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, is not a “trendy” story. Well, that viral “MaJoHa” incident notwithstanding, of course.

The film “Gomburza” (the proper shorthand) is about history, about figures who weren’t even as flashy as the explosive Gen. Antonio Luna, or the charming boy general Gregorio Del Pilar—both of whom have been subjects of historical films themselves. Compared to these (literal) heroic figures, Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora are more subdued. The story is not about their actions—they didn’t fight in the war after all—it’s about the ideas they nurtured and sparked in Filipinos of their time.

As the film has shown, these three priests aren’t necessarily the action figures in history, but they certainly lit the spark of nationalism that pushed our heroes to act.

This film, neatly presented in four acts, conscious of historical integrity, recently bagged 2nd Best Picture at the MMFF Gabi ng Parangal. It also took home several major awards, including Best Actor (Cedrick Juan, playing Padre Burgos), Best Director (Pepe Diokno), Best Cinematography, Best Production Design, Best Sound Design, and the special Gatpuno Antonio Villegas Cultural Award.

Becoming the most-awarded film of the festival, I think points to several important things.

First, is that hope seems to be restored for the annual film festival. After much-repeated discourse over the “quality” of MMFF films, we see the 2023 lineup filled with gems like this (Best Picture and Best Screenplay is the beautifully tear-jerking fantasy film “Firefly”).

[READ: Catch 49th MMFF Best Picture ‘Firefly’ (and more) in LA this 2024]

The second point is another one of hope, this time, for our collective willingness to still remember our past. At a point where history has been subjected to contention, even twisted and weaponized for others’ gain (ahem, politics), this film being made is both important and timely. And the fact that audiences have received it so well even before the official awards were given means there is interest. This is a good sign for filmmakers. It gives us hope that viewers are ready and open and are looking for these kinds of stories.

In a deeper and more nationalistic sense, it’s also beautiful that we get reminders like this once in a while. Reminders of what we’ve been through as a nation, who we were and who we are as Filipinos, and what it means to be one.

Of questions, and a spark of light in our history

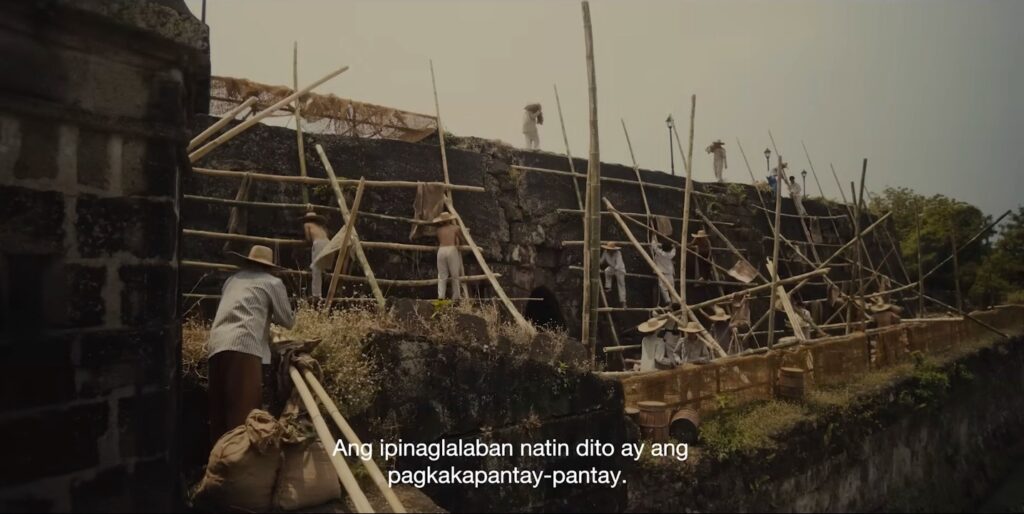

While “Gomburza” markets itself as a film about the martyred priests who ignited the hearts of Filipinos (“nagsindi ng alab sa puso ng mga Pilipino”), it also comes as a slow burn. It takes its time, setting the context, taking its audience through significant church conflicts and injustices that in turn become the flint against which the spark of the “Filipino” identity is formed.

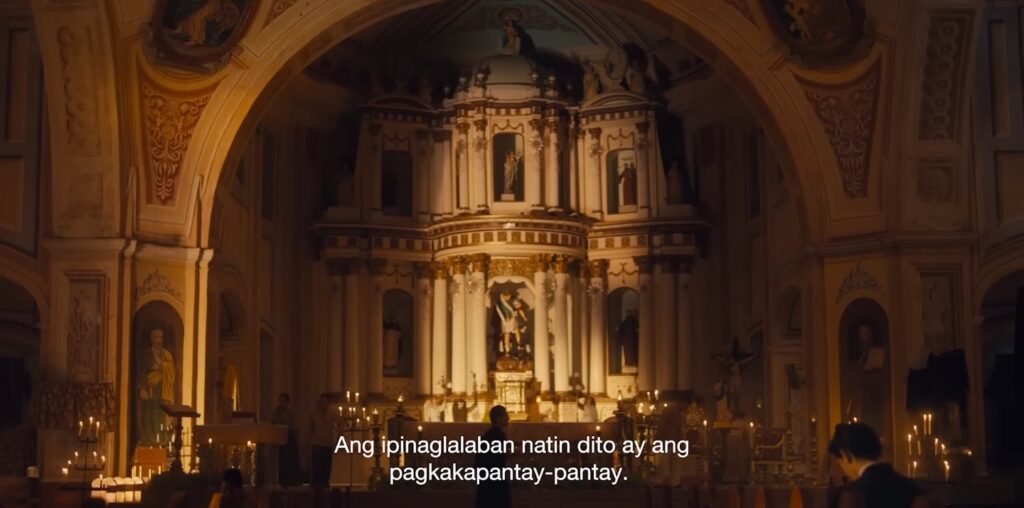

Because it took so much care (time) with its historical accuracy, the first few acts may come across as slow, especially if you juxtapose it against other recent historical hero films. But one must also actively remember that the film’s protagonists are not revolutionaries on the battlefield; rather, they are clergymen, whose life and work revolve within the walls of the church and the college.

In this historical film, the emphasis is on the conversations. It is through the conversations between Burgos and his fellow priests—his mentor Pedro Pelaez (played by Piolo Pascual), his senior Gomez (played by Dante Rivero)—and his students Felipe Buencamino (Tommy Alejandrino) and Paciano Mercado (older brother of Jose Rizal, played by Elijah Canlas), that these characters’ personalities, ideas, and sensibilities come to light.

It takes a while, but perhaps deservedly so, after all, these personas don’t get talked about in depth in the little that our high school Hekasi classes may have touched upon. At most, we are told that it is through their deaths that the national consciousness was planted in many of our heroes.

Many also point out that despite being the protagonists of the film, things mostly happen to the three priests, and not so much them actively seeking out the “action.” But it is through how they react to the circumstances thrown at them that we see their character, and we see how these responses move the story and history along.

It is in the final act that we get delivered the strongest punches.

We see the effects of these injustices and circumstances on different people, and how each one responds to it. There’s something haunting and devastating about Zamora’s (Enchong Dee) visible descent to despair upon learning their fate. From being an easygoing young priest (whose only fault may have been that he enjoyed too much card games), to having gone off the deep end, you end up feeling for him. He was dragged into the situation, exacerbated by misinterpreted evidence against him (an invitation to a game of cards saying to bring “bullets and gunpowder” as a euphemism for gambling money).

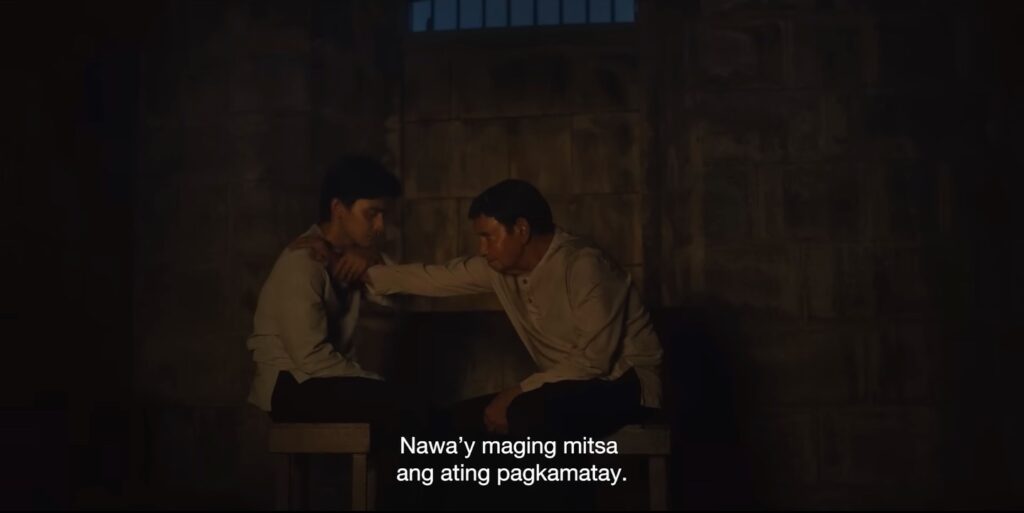

And as Burgos and Gomez, in their final moments leading up to their summary execution, reflect on their and the Filipino people’s fate. It’s a rousing moment when he talks about how ill-fated Filipinos are—even more gut-wrenching when you realize that 150 years later after their death, Filipinos still seem to be getting the shorter end of the stick. (We repeat history, as they say.)

When Gomez, true to his faith, reminds the much younger Burgos that this is God’s will, we see Burgos’ humanity. Is it God’s will that we die, Burgos asks—a very natural, human response, that makes him even more relatable to the audience. Gomez’s response in turn makes him deserving of being called a martyr: that this life, this situation, is part of a grander plan, that their purpose is to ignite a fire in those who will be left to follow after them.

And it does. The spark catches fire, so to speak. In the final scenes, Burgos, bright, young, and fiery as he is, insists on his innocence, down to the very moment he walks to the garrote. A noteworthy, chilling moment (that was also written in renowned writer Nick Joaquin’s “A Question of Heroes”) is when as Burgos asserts his innocence, he is told: “So was Jesus Christ.”

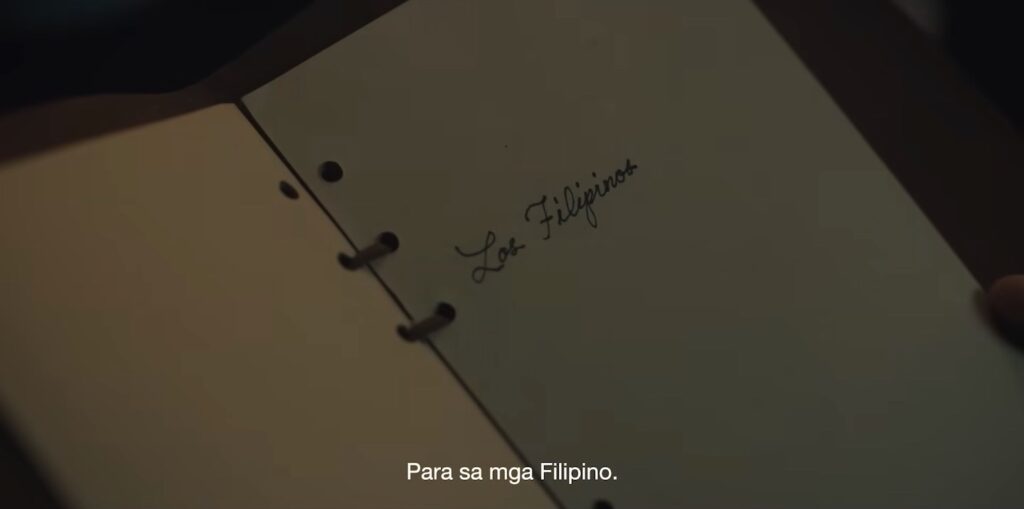

And who to witness all this—Burgos in a final act of protest, raising his fists as the garrote tightens against his neck, Filipinos who have come to witness falling to their knees in shared grief—but the young Rizal. The image must have seared so clearly into his memory, that he continued to carry what the priests and their deaths stood for, well into adulthood. His novels, “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo,” with the latter directly dedicated to Gomburza, are yet another spark being passed to ignite the flames of change in the country.

Aside from shedding light on a part of our history that often gets eclipsed by the louder shouts and bangs of the revolution, the beautiful thing about the “Gomburza” film is that it also served to humanize these martyrs. It is not mere hagiography, nor a purely idealistic, inspirational tale. It shows us the shades of humanity in the people in our history, their light and their shadows. It shows us the birthing pains of the Philippines as a nation—a people.

Well-made historical films like this come once every few years, owing of course to the painstaking work that goes into it. What perfect timing for “Gomburza” to be made and shown today.